Fifteen years after the United States invaded Afghanistan in its pursuit of Osama bin Laden, Afghanistan’s future is as uncertain as it has ever been. Like the Soviets before, America has found Afghanistan a country easy enough to occupy, but hellishly difficult to hold. It was quick to topple the Taliban government, which had offered sanctuary to bin Laden and many of his al-Qaida affiliates, but America has struggled to prop up an alternative government in Kabul capable of governing the entire country. And the Taliban have never really gone away.

For all practical intents and purposes, Afghanistan continues to be a war zone today. As the United States and its allies have withdrawn most of their forces from the country, the Afghanistan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) has struggled to fill in the security vacuum. In this environment, opponents of the Western-backed Kabul government have thrived and expanded their reach. Foremost among these groups are, once more, the Taliban. But there are many other groups running amok in the country, some associated with the Taliban, such as the Haqqani Network and Hezb-e-Islami, others hostile to them as well as Kabul, such as the ISIS Afghan offshoot, IS-Khorasan.

As things stand, there is no reason to believe that things will get better any time soon. Quite the contrary, there is plenty of reason to expect that things will take a turn for the worse.

Faces of combat: Afghan National Army Soldiers >Flickr/ResoluteSupportMedia

The Security Situation

The fundamental problem Afghanistan has is the problem that failed states in general have. And that is that there is not one single organized body of people that can assert a monopoly over the use of force in the region, as per the Max Weber definition of the state.

The main military actor in Afghanistan for the past 15 years has been, without a doubt, the United States. To be sure, the combined might of the United States and its allies would perhaps just about manage to achieve such a monopoly if America’s military strength were not so stretched by its involvement in so many conflicts around the world, in Iraq and Syria, but also on NATO deployments in Eastern Europe, and in its ongoing struggle to contain China in the South China Sea. But more significantly than the sheer military capacity, the United States also lacks the will to invest the necessary resources, military and financial, into securing the country. And even if the U.S. did, it would still be politically problematic for it to actually attempt to do so, because the whole thing would smack of colonization. And the response of the international community to such a development would be quite predicable.

America’s continued involvement in Afghanistan, even drastically reduced as it stands today, is effectively a bottomless pit for American military lives and American taxpayer dollars. Yet the U.S. finds itself forced to keep throwing all these resources into the abyss, lest an even worse outcome prevail. Afghanistan is not a country that is particularly rich in natural resources, or especially fertile. It is not very densely populated, and its population is not especially educated and capable of sustaining production that would be competitive in the international markets. Their prospects for economic development are pretty dim. But the mountains of Afghanistan seem to be an endless spring of militant young men, willing and able to take arms for whatever cause, as has been the case for the region’s long and ancient history. And these proud products of the Pashtun warrior culture have no lack of causes to rally for, in today’s world.

A Scottish soldier talks to local children. >Flickr/Defence Images

The second main actor in the Afghanistan conflict are the Taliban. And they seem to have been the most successful so far at rallying the Pashtun warriors to their cause of liberating the country from Western occupation and re-establishing the indigenous Islamist regime that they had established in the 1990s, after successfully repelling the other major occupation in recent history: the Soviet occupation of the 1980s.

Given the Taliban’s historical track record of having successfully ejected the Soviets — an event that has no doubt also contributed to the ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union — and being the last group to have successfully established state rule in the 1990s, after a similarly long and drawn out conflict, they are perhaps the group that is most likely to emerge as the new state power in the territory, if things continue on their current trajectory. The Taliban have demonstrated incredible tenacity facing off the world’s two top powers in the last 40 years, and that longevity also demonstrates their capacity to endure over successive generations and successive leaderships. As things stand, the Taliban control over 30% of the country, and there is no reason to believe that they are going anywhere soon.

The last major player in the conflict is, of course, the Western-backed government in Kabul. This government has come a very long way since it first emerged under Hamid Karzai in late 2001, but it is still painfully clear that it cannot keep the peace without the backing of the U.S. This has been demonstrated particularly well in recent months with the rapid scaling down of the U.S. presence in the country as Barack Obama nears the end of his presidency and is looking at exiting militarily from anywhere he can. The Afghani government barely controls about 65% of territory, down from over 70% at the beginning of this year.

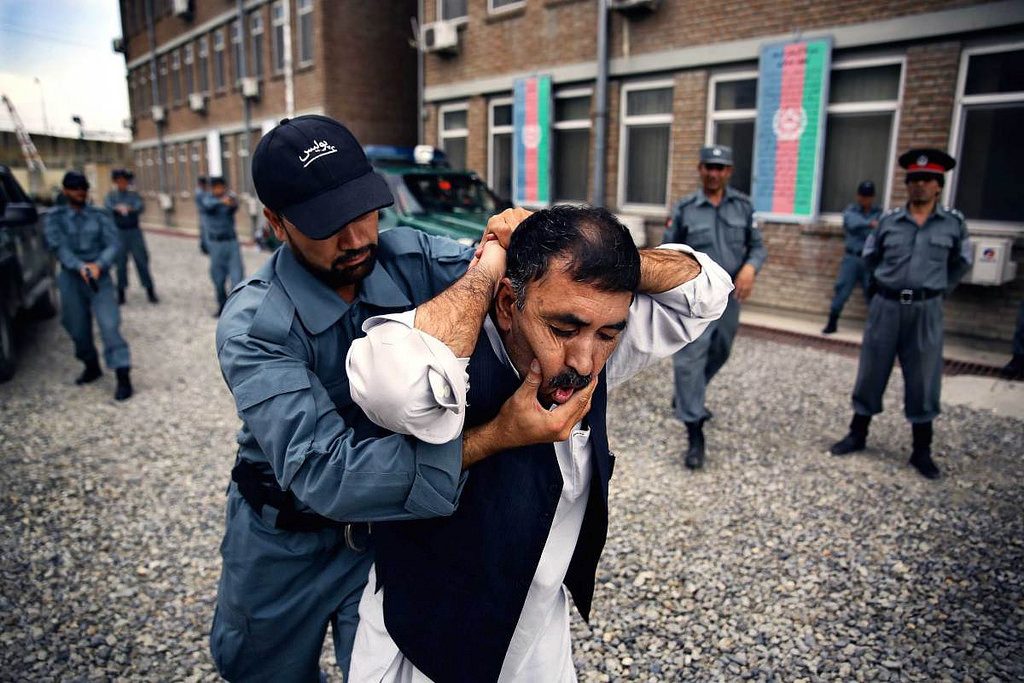

But the problems for the government run much deeper than just its weak military capabilities. Strictly speaking, it should still have the military upper hand over the Taliban, in terms of men and equipment. But Kabul also suffers from chronic administrative problems, not least because its governance structures are not themselves unified and cohesive, especially as one moves away from the capital. Provincial governors ruling on behalf of Kabul have variable, but typically large degrees of independence from central governance. More often than not, these governors have as long a history in the country’s half-a-century on-again-off-again civil infighting as their local Taliban rivals.

Their rule does not look substantially different to the rule of the local warlords who controlled the country immediately after the Soviet withdrawal and before the Taliban takeover in the 1990s. And they are similarly prone to human rights abuses as the Islamists, with ample reports of extra-judicial violence and killings against civilians, intimidation, theft of property and sexual abuse of women and children.

Outside these three main actors, there are a number of other, smaller players, who are also complicating the picture. The most notable, from the point of view of Western security concerns, is the local offshoot of ISIS, IS-Khorasan. As things stand, it is primarily composed of foreign fighters — unlike the Taliban, who are mostly indigenous Afghans, or at most Pashto Pakistanis — and is typically seen by the local population as hostile as other foreign invaders, not least because it has also brought with it the gratuitous excess of violence practiced in the Levantine conflict, and which would make even the Taliban blush.

When IS-Khorasan first entered the conflict, observers watched with dread and feared the worst. But as things stand, it is not fighting only against Western forces and the Kabul government, but also the Taliban and very hostile local populations. IS-Khorasan does not seem to pose a real threat to either Kabul or the Taliban. But if it becomes enough of a threat, it may lead to some degree of coordination between the two to stamp IS out.

All in all, the West remains committed to the preservation of the government in Kabul for the time being, but is unwilling, and perhaps unable, to do more than the minimum necessary to keep it struggling along. From the American point of view, Afghanistan is unwinnable, so the best the U.S. can hope for is to minimize the expense and involvement required as the conflict rumbles on indefinitely. In these circumstances, the only genuine prospect of the conflict ending is by some sort of settlement between Kabul and the Taliban. This was supposedly on the cards early last year, but when it emerged that the U.S. had successfully killed the previous Taliban leader in 2013, the new leadership disavowed the talks and ordered the intensification of the fighting. The leadership will continue to pursue this course for as long as it keeps gaining ground, but we may hope that it will be once again open to negotiations, some time after it is once again held back to a standstill.

Alternatively, some extreme developments could shift America’s perception of the value of the Kabul government if incompetence and human rights abuses get even worse, or perhaps a shift in the U.S. strategic goals in the region, say with the election of a President Donald Trump. If that were to happen, we can expect the U.S. to withdraw and let Kabul fend for itself. Whereby we can expect that a long and protracted conflict would ultimately conclude with a Taliban victory, or at least some kind of peace deal where the Taliban come out on top. That is, unless Kabul finds another sponsor willing and able to sustain it. Possibly Russia, but more likely China, which would be keen to avoid having an Islamist state on its border, if it can help it.

In all cases, the chance that the fighting would stop in the next decade or so is minimal.

Afghan National Police officers during a training exercise. >Flickr/Jordi Bernabeu Farrús

The humanitarian consequences

So long as the conflict persists, the people of Afghanistan will continue to suffer attacks on life, limb and property. In this aspect of the conflict, there really are no “good guys.” The worst excesses are perpetrated by the foreign fighters of the Islamic State, as per their propaganda strategy. The Taliban have a pretty bad reputation for human rights abuses, and according to NGO reports, are typically responsible for two-thirds to three-quarters of reported attacks against civilians. These attacks fall disproportionately on women and other minorities, in response to the West’s promotion of rights for these groups, and none are targeted more than elected representatives in the government who are women. Any shift in the power-dynamics between tribes and ethnic groups that result from Western-led initiatives is likely to provoke fierce resistance from those who feel they are losing long-standing privileges.

But for all the progressive rhetoric in the meeting halls of Kabul, out in the country, Kabul’s governors and their local militias are still accountable for over 15% of attacks against civilians, including rape, child abuse, forced evictions and expropriation of communities and so on. This is noticeably less than what the Taliban and other Islamist groups do, but they are still egregious numbers for institutions that fancy themselves the legitimate government of the country.

Nor must we forget the “collateral” civilian victims of the deployed Western forces. As the total number of foreign fighting troops in the country are tumbling to below 20,000, significantly fewer than both the ANDSF and the Taliban, and as they have been slowly transitioned out of the front-line fighting roles, their figures look much better. But the U.S. Air Force has bombed a Doctors Without Borders hospital killing 40 as recently as last autumn.

All in all, after the 40-odd years of infighting, the country seems to suffer from a generalized culture of violence, and crimes against civilians are commonplace. We cannot foresee that things can get much better while the conflict is ongoing, and perhaps even after it will have died down, human rights will take decades and several generations of incremental improvements, before it would reach acceptable standards. And this is provided that nothing happens to make the conflict take a turn for the worse.

For these reasons, the future of Afghanistan for the next half a century looks bleak. The chances that the conflict might end any time soon, either by dealing with or by defeating the Taliban, are vanishingly small. Nor is there any real commitment to making this happen, or indeed, anyone obvious who could make it happen. In the past year, Afghanistan has produced the second highest number of refugees, after Syria. As things stand, there will be many more to come.

This article appears in the Summer/Fall 2016 print issue of The Islamic Monthly.

The magazine can now be purchased with print on demand! Click on this link to purchase a single issue.