Becoming what people have called “The Face of the Resistance” has garnered quite a bit of attention and curiosity toward who I am and my story. I’ve received interview requests from journalists based here in the United States, as well as abroad. At first it was all very unexpected and rather daunting; I could barely keep up with the emails and scheduled Skype calls/phone interviews. To hear from so many respected international publications and media outlets also caught me by surprise. After a while, I started noticing that the majority of the press inquiries were coming from media based in other countries. So, it didn’t come as a complete shock when weeks later, I dug through my Facebook inbox’s spam messages and found a lengthy message from a Lebanese producer that had been filtered as junk.

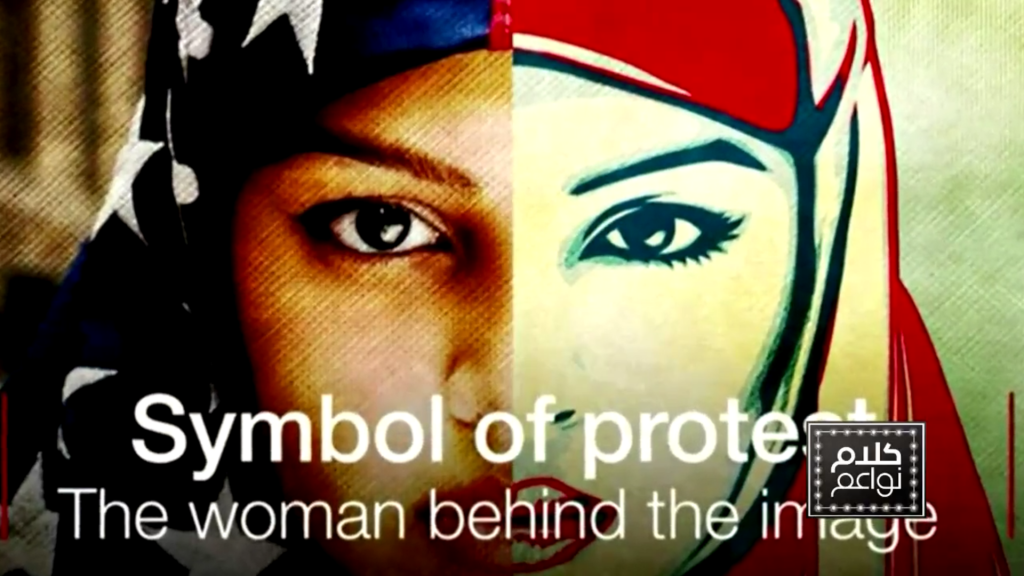

The producer, Rana Daher, had seen the famous poster and heard me speak with the BBC and The Guardian. She invited me to come to Beirut, all travel and accommodation provided, to be a guest on the Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC) network talk show “Kalam Nawaem.” The MBC is a massively popular and influential network in the Arab world, and “Kalam Nawaem” was described to me as their equivalent of “The View.”

Her offer caught my attention, but I wanted to gather some feedback before deciding, so I started to ask friends and advisers what they thought I should do. The initial reaction from many of these people was concern. Did I really want to go to a Middle Eastern country right now? What if there was a terrorist attack? Would I be given bodyguards in case extremists recognized me? Could I be safe as a woman there, traveling alone? One friend wasn’t so much concerned with Lebanon, but what would happen on my return. Would I be allowed back into the country? Would I be detained at customs?

These are the sort of questions I received from my concerned friends, with some even telling me flat out not to go. I’m also an empath, so I worried about how the trip would affect my energy, knowing the possibility that I’d come upon the visible remnants of the war with Israel, and that labor workers who migrated from impoverished nations are treated unfairly in many Arab ruling nations, especially workers from Bangladesh, Ethiopia and the Philippines. The things I know would break anyone’s heart.

I considered the possibilities. I’m an American citizen, born and raised in New York City. Lebanon also was not listed as part of the travel ban. On paper, it appeared I was in the clear. But one of the concerned friends felt it would be wiser to “wait until things settle down.” I decided to speak with Van Jones, the commentator and author. He presciently told me that things may not calm down. That aligned with my intuition, that perhaps things would get worse before they start to get better. Maybe there wouldn’t be a break in the storm until another president comes into office. So, right now could very well be the optimal time to go. I let Rana know the yellow light had just turned green.

After a couple weeks of correspondence and confirming logistics, I was finally headed to Lebanon. I made my way off the plane and into the terminal at Beirut-Rafic Hariri Airport. My flight was delayed from a long layover in rainy Istanbul, but luckily, I spotted the driver they sent for me who was holding up my name. Walking out with him to his car honestly felt like I was walking through LAX. It was a beautiful sunshine-filled day. There were palm trees everywhere, and the city was glowing. Once I reached the hotel and checked into my room, I fell into a deep, jet-lag-induced nap. At that point, it was mid-afternoon.

By the time I woke up, it was somehow already 11 at night, and I realized my phone’s charger was not in my belongings. I recalled last seeing it when I had it charging at my seat on the plane, so that had to be where I had forgotten it. This was a very specific type of charger too, the Universal Type-C. I wouldn’t be able to simply borrow someone’s Android (micro USB) or iPhone charger. With the little bit of juice I had left on my phone, I connected to the hotel’s Wi-Fi and looked up cell phone accessory stores in the area. I found a couple that were listed, and then Google mapped their locations. I decided that first thing in the morning, I’d head out and keep my fingers crossed they actually carry it. Not many tech accessory stores in New York even do. Being out and about on foot would be the moment of truth. Would my concerned friends be proven right? Will I, at any point, feel unsafe?

The next day

Thankfully, they were wrong. It was more than a pleasant experience. I felt totally safe, wasn’t cat-called at all even while walking past groups of men, who respectfully did not ogle. I got to roam in peace, find and purchase this elusive charger, and also take in the beautiful streetscapes that the neighborhood of Hamra has to offer. Throughout the rest of my five days there, I experienced so many sights and sounds that needed to be captured and shared. I updated my Instagram stories whenever I got the chance, and the responses from my friends were so positive. Many told me they had no idea Lebanon was so stunning, and quite a few told me my images were inspiring them to make a trip there in the future.

After a lovely day exploring the Farmers Market at the Beirut Souks and Zaitunay Bay, all on foot and without anyone accompanying me, I headed back to the hotel to get ready for the show taping. They sent a driver to bring me to the MBC studios in Jounieh. After hair and makeup, I waited in the green room with some of the other guests. My nerves were for sure on edge, but not to the degree I thought they would be. I was more nervous to meet the hosts of the show, who are celebrities in their own right, than I was about being part of a high viewership television program. Eventually, I was brought out to do the taping of my segment. There was a video vignette to introduce me, and a live studio audience, very much like “The View.” One audience member yelled out, “You are beautiful!” as I came out. (If you’re reading this, thank you kindly; I had momentary stage fright.)

Some of the questions that were asked by the show’s two hosts, Nadia Ahmad and Muna AbuSulayman (and one guest co-host, Mayssoun Azzam), were expected, while others were not. But all the dialogue and discussion that came about was welcome, and necessary. I felt I held my own and was really glad and grateful to have the opportunity to share my story. Also, having my first on-TV appearance be directly viewed by a largely Muslim audience was important. I know that millions around the Arab world, as well as Arab-speaking households in Europe and America, have seen it, and I felt honored to be there as a voice speaking on behalf of Muslim Americans. I also made sure to mention that my experiences are not everyone’s, and that my views are my own and not shared by all.

I spent the remainder of my trip being hosted by Nadia, and through that experience fell even more in love with Lebanon. There were times it was reminiscent of being in a Mediterranean city in southern Europe, in the best way possible, just that most people were Arab. I could see why it was once called “the Paris of the Middle East.”

There was a vibrant LGBT community that existed openly, without shame. Christians and Muslims living peacefully side by side, from what I observed. It was Palm Sunday and I felt like the Muslims there were just as excited for the Christian festivities. Women of whichever faith dressed as comfortably as they desired amid the Mediterranean heat. I happened upon a day party on Uruguay street with a line-up of 10 DJs back to back, and noticed there was no tension about attendees drinking alcoholic beverages in public. The photographer side of me was feasting on all the gorgeous picturesque views inside and outside of Beirut, lovely coastal towns such as Harissa, Byblos and Batroun. It was a blessed experience, and truly humbling to look back now and think about how much love I was shown by the country and its people. That made it very hard for me to want to leave.

- Processed with VSCO with c1 preset

On my way back to New York, I had a long layover in Rome, so I took the opportunity to explore a bit of Italy for the first time as well. I made sure to visit the Colosseum, as well as consume some fine Italian gelato and authentic pizza. I can honestly say I was on cloud nine coming back, absolutely immersed in positivity and gratitude for all that had taken place in the past week. I even managed to fall sleep on the flight, tired from walking all over Rome with my backpack, but also very much at peace with how this entire trip went and fell into place. Getting to rest at that high of an altitude usually does not come easy for me.

After nearly 10 hours in the air, we arrived at JFK. As I disembarked, I prepared for what I had come to know over the last few years of traveling abroad, and was not surprised to be met with more of the same nonsense. Every time I fly into JFK airport, I get placed in secondary holding at customs. This is a recurring problem that existed for me way before our current president ascended to power, so it would be too easy to blame it on his administration. It also has never had anything to do with where I’m traveling to or from. It has everything to do with my Arab first name and surname, presumably marking me as Muslim.

After I got the “X” on the printout that the passport scanning kiosks give out to “randomly selected” individuals they want to question, I was brought into another room, filled with other people, who largely looked to be either Arab or Muslim. There was not a single White person in sight unless you counted the border agents. We took a seat and just silently prayed this wouldn’t take forever. Chances are it would. The officers were doing more banter with each other than actual work to expedite the process.

There was a moment during my endless wait when my phone rang. My immediate instinct was to pick up the call so it would cease to continue ringing. It was my mom calling me to tell me that my uncle, who drove to the airport to pick me up, was waiting outside the terminal and tried reaching me multiple times to see where I was. During this ordeal, I had totally forgotten that I sent him a text before boarding in Italy, to see if he was available to pick me up. I tried quickly and quietly to tell my mom that I landed but am stuck in holding, but was immediately shouted down by the agent in the room, who scolded me like I was a child to hang up the phone. His tone was completely devoid of any respect for me or my autonomy. I would’ve hung up just the same if he had simply stated, in a respectful tone, “Excuse me, no calls allowed in here.”

As I ended the call, the last thing I heard was my mom saying, “What? I can’t hear you. Where are you?” Once again, my instinctual plan of action was to immediately send her a text letting her know what had happened, at which point the same agent proceeded to yell at me again, in a far more berating tone. This time, he was forcing me to give up my phone to him. If my uncle wasn’t out there waiting, unaware of the circumstance of my delay, I would have absolutely told this brute of a man that he would not be in possession of any property of mine without my lawyer present. But I did not want to give this person further reason to keep me behind any longer than I was made to already. Who knows? Perhaps, even worse could have happened. People in those roles tend to act out in dangerous ways when they feel their authority is questioned. Our country does not always prosecute those who abuse their power.

Once I was released, and in the comfort of my uncle’s vehicle, the feeling of rage over what I had to put up with did not suddenly dissipate. I was antagonized, and made to feel embarrassed while having to sit in that awful room, a room I ended up in for no reason other than because I am a Muslim woman who travels and now wants to sleep in her own bed, in her own city. This country has been home for me all 32 years of my life. I have no other nationality beside American, and I never have. So why am I made to feel like I shouldn’t belong here and need to be screened every time I re-enter from elsewhere?

The experiences stuck with me, as they always do, but this time felt much worse. The irony I’m drawing on here is that despite folks who care about me, warning me about Lebanon and the Middle East, I got there, passed my time safely and everything went great. Far better than anyone, myself included, could have imagined.They assumed I would be safer not going, pleading “just stay in America for now.” And yet, reaching American soil was where I felt my identity as a woman and brown person was most threatened and the possibility of harm inflicted unto me. I feel sometimes like I’m more a citizen of the world than a citizen of America, especially in situations like this where I’m more embraced and accepted in other parts of the world than in my own.

Until the day there are actual physical restrictions or financial burdens that prevent me from traveling, I doubt I’ll ever stop, because it’s who I am. It may very well be part of my DNA. Seeing the world and making connections across cultures brings me joy and personal fulfillment unlike anything else. I’m always curious and exploring. Even when I’m here in New York, I’m researching places and things and foods and languages and customs on the other side of the planet and even places close to home.

America’s tendency to discriminate against Muslims won’t stop me from getting out there and living out the rest of my journey wherever it takes me. I am, however, going to apply to the Global Entry program, despite the cost and tedious process, just for the assurance that I can at least return home in peace. It is unfortunate that I’m having to take extra measures, not for the luxury of saving time or to avoid the inconvenience of standing in lines, but because this is literally the only way I can be treated like a person. I’d like to know what it feels like to be a citizen of my own country for once.

*All images via the author.