Last month, President Donald Trump made his first foreign trip as commander in chief of the United States to Saudi Arabia. That nation plays a critical role in U.S. foreign policy and is integral in the fight to combat violent extremism largely emanating from the Middle East. In his keynote address at the Arab-Islamic American Summit in Riyadh, Trump said, “I chose to make my first foreign visit a trip to the heart of the Muslim world” to promote a unified position between the U.S. and the Muslim world to stand against transnational extremism. As I watched the speech live on my flight across the Atlantic Ocean from an international conference where I presented on how Western communities can remain resilient against violent extremism, I couldn’t help but think about some of the insights from my presentation and particularly my own personal experience as a third-generation Black American Muslim.

Let’s be clear, though Islam began in the Arabian Peninsula, the Arab world is not where most of the global Muslim population resides. Recent texts, including Harvard Professor Ousmane Kane’s Beyond Timbuktu and Boston University Professor Fallou Ngom’s Muslims Beyond the Arab World, highlight the importance of Islamic thought and intellectual knowledge emanating from outside the Arab world. Recent polling data, including the 2015 Pew Research Center report underlining the current and projected size of Muslim religious groups globally, offer even more compelling insights. Most importantly, the report expresses the true diversity of Islam and that Muslims are largely non-Arabs. Furthermore, the report indicates that more Muslims live in India and Pakistan than in the Middle East-North Africa region, and some of the fastest growing populations are in continental Europe and the Americas.

All this points to the reality of a global and shifting Muslim demographic, and more specifically, the important role of the American Muslim population — and even more specifically, Black American Muslims — at-large. Despite Black American Muslims having paid the way historically for many mainstream Muslim organizations — like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA), Muslim Student Association (MSA), Muslim Public Affairs Council, Zaytuna College and several other Islamic institutions — the current visibility of Black American Muslims seems to have almost entirely been erased from the public discourse.

What has happened? Where have our communities gone? What has happened to the oldest Islamic school institution in the U.S., Clara Mohammed Schools, and new Muslim communities learning from their sweat and tears?

Even the institutional memory of notable and renowned Black American imams, including Imam Siraj Wahaj, Imam Warith Deen Mohammed, Imam Al-Hajj Talib Abdur-Rashid and leading Muslim activists, has been seen in many mainstream circles as being hyper vigilant on race issues and in some way inferior to co-religionists who often struggle to differentiate between culture and religion largely emanating from their experiences in their country of birth. Black American Muslims are a quarter of the population and represent the largest percentage of American Muslims in the U.S., and are able to be part of all aspects of American society, including being doctors, lawyers, small-business owners and just ordinary Americans with a proud Islamic identity.

Our communities are evolving as we move toward the future. We now represent communities within communities after the legacy of our Black American Muslim forefathers and mothers who established the framework for our entire Muslim community’s existence. For at least the past 50 years, sub-communities among Black American Muslims — including the Ahmadiyya, Nation of Islam, Imam WD Mohammed affiliates, the Dar movement, Imam Jamil Al-Amin associates and numerous other Salafi, Sufi and Shia adherents — have been working hard to maintain the identity of their past and to receive proper recognition for their hard work.

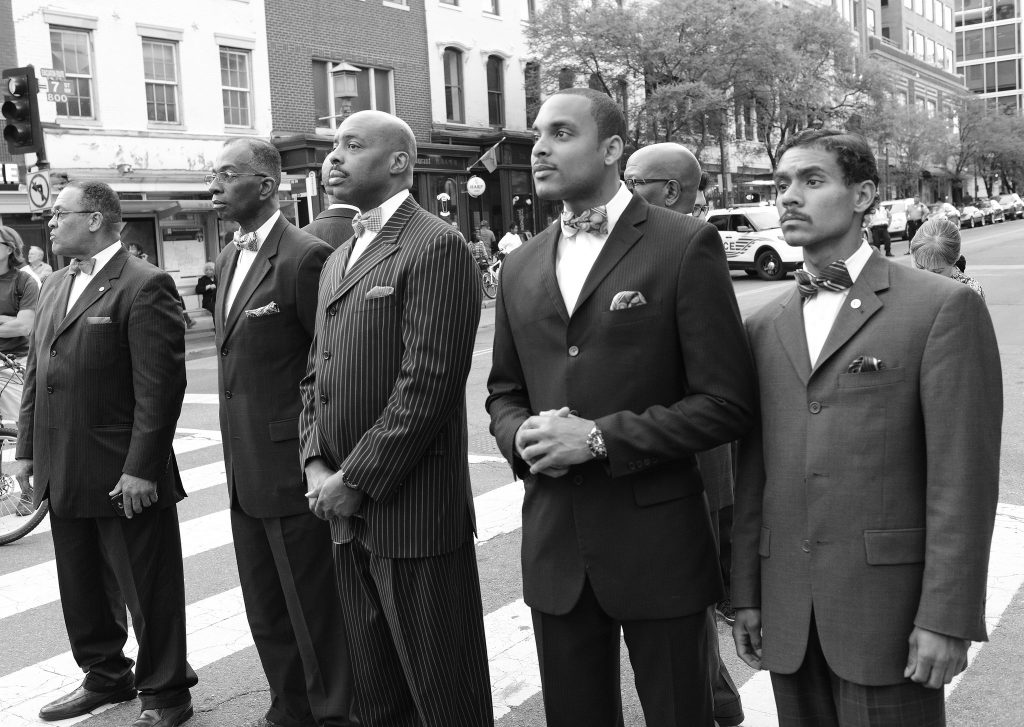

Members of the Nation of Islam at a Washington protest in solidarity with Ferguson > Flickr/StephenMelkisethian

Now, perhaps due to the realities of our communities being third-, fourth- and fifth-generation Black American Muslims, we are seeing an unprecedented evolution. Conservative, secular, cultural and hybrid Muslim identities are developing at a rate that, perhaps because of globalization or societal evolution, is equally affecting our communities. And, millennial Black American Muslims have new relationships and friendships with immigrant Muslims that are sometimes free of our parents’ and grandparents’ real and/or perceived tensions with these communities.

And a steady inflow of new converts (reverts) of Black American heritage, some who are millennials and others who are new to the faith, are also aligning themselves with al-Qaida and the so-called Islamic State, challenging how our communities respond to this global epidemic.

Our communities are no longer a monolith. And that isn’t a bad thing. How Black American Muslims seek to respond to this changing reality and build on its inheritance of leadership should offer thoughtful reflection and opportunities within Black American Muslim communities and for their co-religionists of White, South Asian and Arab ethnic identities, to name a few. Black American Muslims make up the largest indigenous Muslim community in any Western democracy, and offer an independent voice free of some of the sectarian pettiness and cultural baggage that has unfortunately permeated communities in the broader Islamic world and some in the Diaspora.

By lending our voices, amplifying our theological and philosophical views rooted in our experiences in America, we can be a voice of balance and reason globally. Without Black American Muslims stepping up to this challenge and providing real and meaningful solutions, the various prototypes of Black Americans who are diverse, eclectic and authentically Muslim won’t be heard. Our voices are needed more than ever.

*Image: Speaker at a rally against Islamophobia in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Flickr/FibonacciBlue.