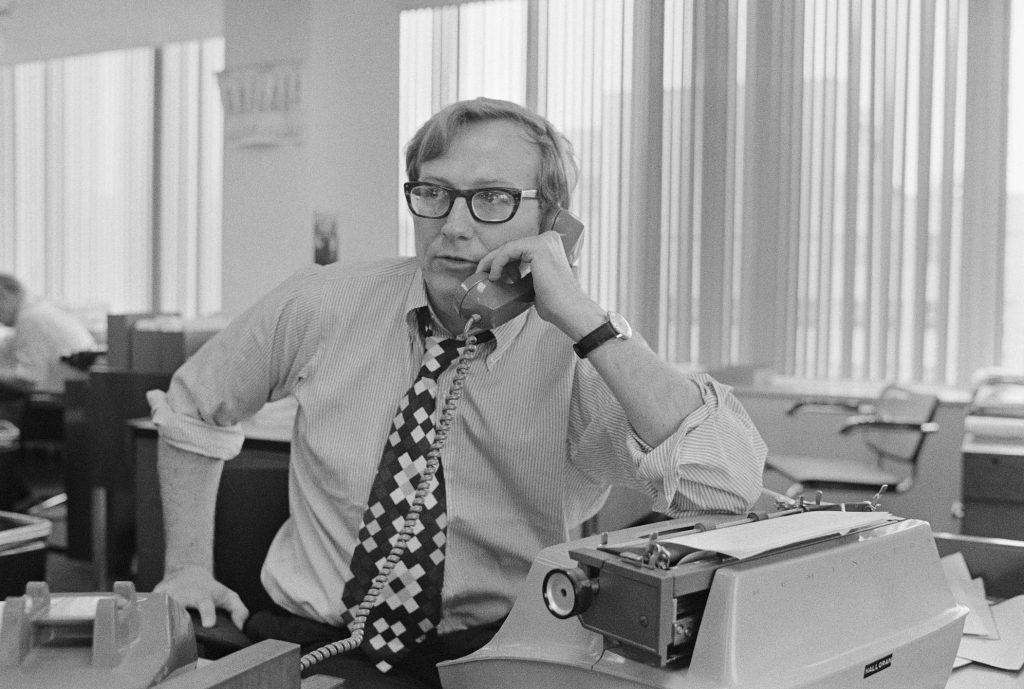

American journalist Seymour Hersh, whose reporting of the 1969 My Lai massacre in Vietnam made him a legend, created some buzz with his latest story in the London Review of Books about the U.S. raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in May 2011.

The Obama administration lied about the details of Operation Geronimo, Hersh argues, and the mission was actually carried out with full assistance from the Pakistani army and its Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Hersh notes that President Barack Obama went public about the death of bin Laden right after the raid, betraying a promise to Pakistan to wait a week and stick to a predetermined script that bin Laden was killed in a remote region of Afghanistan by a drone strike. By spilling the beans and taking sole credit for the operation, Obama threw Pakistan under the bus. The United States, Hersh says, is a superpower programmed to act with arrogance and Obama wished to appear as a strong, cold-blooded leader to buttress his domestic standing before re-election.

Unfortunately, Hersh’s story, apart from being factually dubious, is based on a U.S.-centric paradigm, as if Pakistan does not have its own politics and its complexities can be explained away by simply looking at internal U.S. politics. What is even more striking is that, for an investigative journalist who likes to challenge state narratives, Hersh uncritically accepts the narrative of the Pakistani army and bases all his arguments on the premise provided by former ISI head Asad Durrani. The apriorism on which Hersh’s article rests is this: The United States lusts for power and Pakistan can be bought with enough money. It is precisely this that makes Hersh’s article dangerous and cynical. It offers absolutely nothing in the way of serious geo-political analysis.

While it is true, as Hersh states, that the U.S. and Pakistan are locked in a mutually beneficial relationship, it is nonetheless the case that the allies have competing interests as well. This has been evident throughout the war on terror, as Pakistan has consistently sought to maintain leverage over the evolving situation in Afghanistan and its eventual endgame. It has done so by supporting certain militant groups and sheltering them inside Pakistani territory. As early as the primaries, when he was running for leadership of his party, Obama blamed Pakistan for America’s difficulties in Afghanistan and argued for sterner action against Pakistani duplicity, so much so that even John McCain criticized Obama for being too tough on Pakistan.

It was no surprise then that the Obama years saw U.S.-Pakistani relations drop to a new low. Not trusting Pakistanis to do the job on their own, the Obama administration carried out extensive drone campaigns in Pakistan’s tribal areas to target various militant groups. The point of contention between the allies was not the drone strikes themselves, but that many of the strikes were carried out without the Pakistani army’s knowledge.

The Pakistani army is usually cooperative with the United States in counterinsurgency operations, including drone operations, though only when the targets are militants whom Pakistan also wants liquidated. When the United States began targeting militants who were still useful to Pakistan, relations between the countries deteriorated quickly and the feud became public. The trust deficit between Pakistan and the United States has been a major feature of the Obama years.

The raid that killed bin Laden and the ensuing Pakistani reaction point more toward this dynamic rather than the kind of relationship that Hersh outlines. Pakistanis’ immediate reaction to the raid was utter shock and anger. The army felt publicly humiliated as it was helpless to stop another country from coming inside its territory, carrying out an assassination and leaving — all undetected. In the past, when Pakistan handed over al-Qaida operatives to the U.S., it made sure not to allow American operatives anywhere near the target. But this time, the U.S. did not even bother to inform the Pakistanis. For the eighth-largest army in the world and the self-proclaimed protector of Pakistan, it was as if the ground beneath the Pakistani army’s feet had disappeared. To control the damage immediately after the raid, the Pakistani government told its diplomatic mission in Washington, D.C., to draw up a case of defense by accusing the United States of violating Pakistan’s sovereignty. They were also concerned that Pakistan would be accused of harboring a terrorist.

Contrary to Hersh’s claims that the U.S. left Pakistan high and dry by going off script about the raid, Obama actually saved Pakistan from embarrassment by initially crediting the country for its assistance in apprehending bin Laden. Despite the fact that the world’s most-wanted terrorist and America’s enemy No.1 was living as a next-door neighbor to Pakistan’s largest military academy — something that could not have been possible without inside collusion — Obama did not accuse Pakistan of sheltering a terrorist. This was a favor done to Pakistan since it protected Pakistan from international scrutiny. Like a true ally, the United States shielded its partner when it did not deserve it. The question of how bin Laden was living undetected in one of the most sensitive areas of the country did not come up. Pakistan was never taken to task. Even though the U.S. changed the narrative and took sole credit for the operation — and Hersh could be somewhat right in saying this was due to Obama’s desire to show himself as a strong president — Pakistan was still left off the hook.

A hyper focus on Washington’s narrative about the raid misses the point. Whether Pakistanis were involved side by side the Americans or whether the U.S. betrayed the Pakistani army is a matter of practically zero consequence on the realities of the war on terror. So what if Obama took all the acclaim for the operation? What should have been a focus of the debate instead is the kind of ally Pakistan is and the unacceptable support it gives to jihadis inside and outside its borders. The consequences of Pakistan’s support for terrorist groups is not limited to massive loss of Pakistani lives during the past 14 years, but every major attack and attempted attack in Western capitals and in India have been linked to Pakistan-based jihadis. But Hersh’s article, fixated on inconsequential facts, not only glosses over this Pakistani policy but may even sit well with it. Hersh asks no questions of Pakistan; in fact, he directly cites Durrani as an endorsement of his article by saying the Pakistani people will appreciate the truth. What truth exactly? That Pakistan took part in the mission to kill bin Laden? Or that Pakistan was knowingly hiding a terrorist right next to a military academy? Does Hersh think Pakistanis should appreciate knowing their army played a part in the mission? Or should they rather not be embarrassed and angered with their army for supporting bin Laden? What right has Hersh to decide what Pakistanis should appreciate? Who is he to tell Pakistanis it is more important to know that Washington was lying rather than their own government’s duplicity and double-game?

Ever since the raid, there has been deep panic and anxiety inside the Pakistani army because its aura of invincibility had been destroyed. The army, which prides itself on its efficiency in contrast to the civil government, was made to look just as incompetent and unaware as the rest of the state. Not only was the world’s most-wanted man living in a garrison town, but another country managed to penetrate the border without the Pakistani army doing anything about it. The issue is not bin Laden; the issue is national honor.

How to make amends? Promote the narrative that Pakistan was in fact involved in the capture of bin Laden from the beginning and that the U.S. could not have completed the mission without Pakistani assistance. Blaming the U.S. for being ungrateful slots in well with the existing narrative in Pakistan that the U.S. is generally an unthankful ally that does not value Pakistani sacrifices in the war on terror.

Sadly, Seymour Hersh, in his single-minded drive to prove that Washington lied about the entire mission, does not attempt to understand how Pakistan works. He has actually become a useful ploy for the Pakistani army to try to clear its name and regain its lost pride.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 print issue of The Islamic Monthly.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 print issue of The Islamic Monthly.