I was in sixth grade when I heard my mother cry for the first time. Her brother Booker T. was killed, the only brother of her five siblings. He was one of the few relatives who visited us in California, and we stayed with his family when we travelled to New Jersey. The details trickled in as she scurried to make arrangements to fly from California to New Jersey. Cops warned my aunt that day that if he got into any more trouble that they’d take him out….money owed…standoff…he put the gun down.…he was shot 37 times…a boy in the house died in the hail of bullets. My mother didn’t get a chance to say goodbye. The police morgue wouldn’t release his body. My uncle had previous run-ins with the law, but the official report differed from witness accounts. The final insult was reading about the stand off in our local newspaper which described the standoff as a sanitized version of the events. My uncle was nameless.

Gun violence, police brutality and stand your ground laws makes the United States a dangerous place for all black people. Black women across the nation have suffered with moments like seeking help after an accident, jay walking as a black female professor, or disoriented due to mental illness. But the profiling of the black man remains intense to this day, as it has for most of American history. My mother, when we were all younger, moved our family to the suburbs with hopes that it may insulate us from some of the problems of the inner city, but it did not insulate my brother from being profiled, from being pulled over for non-moving violations, getting hauled off to jail from time to time. A few times, I remember my mom yelling on the phone, then heading out to threaten the police with legal action if they didn’t release my brother once jailed. As a single mother, she did whatever she could to keep her son out of jail, where we knew that any small infraction could send him, like other young black men around the country, into a downward cycle in the prison system. It wouldn’t take much to target him or others like him: tinted window, loud music, outstanding tickets, wrong paperwork, unpaid child support. And in the moment itself communication would not exist between himself and the officers as he would repeatedly attempt to inform them when forcing his hands in to handcuffs that he couldn’t bend his arm because of a permanently fused elbow. In moments like that, he would have to make a decision while looking down the barrel of a gun or getting forced into handcuffs. Years later, my own husband faced a similar choice, when he was pulled over and the cops pulled a gun on him simply because he “fit the description” of a suspect at large in a small mostly white town. There was no ability to communicate with the officers. After he published his experience, the police constantly pulled him over. The stress drove him to move to another state.

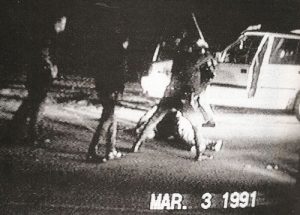

Garner couldn’t save himself even as he became compliant. Eric Garner called for help, crying out “I can’t breath” on six different occasions, and just as my brother or husband had to, would be forced in to utter compliance with no ability to be heard by those officers in charge. We might recall Oscar Grant who was also clearly subdued, leading to officer Johannes Mehserle shooting him. My cousin who witnessed the 1986 standoff said that my uncle put the gun down, yet the officers began, and continued, shooting. I could list other cases, but in the age before smart phones the law was usually on the side of the police officers. But then again, even video could not implicate police officers, as I learned during the Rodney King verdict in 1992.

But in this case there was a video. And it went viral. And I watched as did the rest of the nation. And then, I read about Muslims across the

The Muslim American community cannot sit comfortably in isolation. In fact, our failure to address the realities of black American Muslims is becoming more evident as neighborhoods around inner city mosques crumble and some communities have lost their youth to the streets. Many grassroots programs lack support from mainstream Muslim organizations. There are a number of well-intentioned activist Muslims of immigrant descent who are on the forefront of protesting police brutality and addressing the prison industrial complex, but many of these activists are well versed in secular activism and often by-pass initiatives led by black American Muslims, which only further marginalizes black Muslim voices. It is time that Muslim social and civil society institutions build bridges and empower the disadvantaged and protest in the same ways that they do for oppressed Muslims abroad or of the government spying of Muslims at home. For many of us black Muslims, addressing police brutality, gun violence, education and health care access is not an intellectual exercise or some activist phase of our youth. It is our very survival. I ask you to care because Renisha is me, Oscar is me, Trayvon is me, Eric Garner is me. And there are millions of us facing this type of discrimination and profiling on a day to day, hour to hour, basis.

Instead of making Islam the solution to society’s problems, our communities have shifted to Islam is insulating ourselves from society’s problems. And that is problematic. And alienating. We should be enraged at Garner’s death. But we should recognize that this happens daily across the nation. And it is happening to a large segment of the American Muslim population too. And will continue to happen, unless we all start to mobilize and organize together.