Why Muslims Need to Act on Mass Incarceration, Detention, and Deportation

aleed: I recently attended a workshop in a Pennsylvania prison where I was taken aback to hear more than a half-dozen salaams from the prisoners who read my nametag, recognizing my Muslim name. We read from a scenario involving a character named Jason who decided to sell drugs and obtain a firearm as his support systems shattered around him. A typo had accidentally turned Jason into Jamaal in the middle of the reading, resulting in much laughter from several of the men.

aleed: I recently attended a workshop in a Pennsylvania prison where I was taken aback to hear more than a half-dozen salaams from the prisoners who read my nametag, recognizing my Muslim name. We read from a scenario involving a character named Jason who decided to sell drugs and obtain a firearm as his support systems shattered around him. A typo had accidentally turned Jason into Jamaal in the middle of the reading, resulting in much laughter from several of the men.

“Sounds like Jason up and took shahadah while dealing drugs,” one of the men said, laughing.

Prisons are deeply embedded in the history of Islam in America. One unconfirmed study has found that anywhere from 17-20% of New York’s prison population identifies as Muslim, with the vast majority converting after being incarcerated. This trend follows in a long American tradition of incarcerated men and women converting to Islam in order to gain a vocabulary for understanding not only the meaning of life, but of racial and economic oppression as well. One of the Nation of Islam’s greatest strengths was its ability to rehabilitate prisoners and those returning from prison from not only their past involvement in a life of crime, but also from the oppressive conditions of prisons themselves.

Malcolm X’s own conversion to Islam while incarcerated allowed him to develop a language of protest and gain practice in advocacy. Before he was known as a leading civil rights leader, Malcolm demanded the right for Muslim prisoners to leave their beds after lights-out curfew to perform the night prayer. In a letter dated November 14, 1950, Malcolm wrote, “This sojourn in prison has proved to be a blessing in disguise, for it provided me with the Solitude that produced many nights of Meditation.”

“The devil’s strongest weapon,” Malcolm continued, “is his ability to conventionalize our Thought…we willfully remain the humble servants of everyone else’s ideas except our own…we have made ourselves the helpless slaves of the wicked accidental world.”

In the aftermath of 9/11 and the War on Terror, many American Muslims, specifically those of recent immigrant backgrounds, became politicized for the first time as they saw their communities turn into targets of routinized suspicion, surveillance, and detention. American Muslims began publicizing and organizing around surveillance on Muslims domestically in our mosques and human rights abuses abroad in secret prisons and the not-so-secret Guantanamo.

While these battles and abuses must continue to be fought and publicized, American Muslims must learn to see the parallels between the War on Terror and other wars on black and brown bodies within the United States.

Activist and Professor of Law at Seattle University Dean Spade provides an excellent model for identifying issues of injustice and effective ways to bring about social and political change, writing:

“If a group is being exposed to premature death through overexposure to pollution, police violence, hunger, lack of healthcare, poverty, homelessness, military occupation—those conditions must be remedied and the systems causing them must be dismantled. Sometimes movements have gotten too concerned with law reform or just trying to get government recognition instead of actually trying to change people’s chances at living. We need to not be satisfied until people actually have good housing, healthcare, education, and all those things that you actually need to live well and thrive.”

The aftermath of September 11th made apparent to Muslims from recent immigrant families what many African Americans and Latinos in this country already lived as reality–what it means to “fit the description.”

To resist these systems, American Muslims must embark on the hard work of community organizing and consciousness-raising. Too frequently, we express our outrage solely through social media, instead of seeing the Internet as a strategy, not an end goal. Janani Balasubramanian of the blog Black Girl Dangerous recently wrote an article critiquing social media activism” which she described as tending “to focus on individual/interpersonal oppressive dynamics.” Our knee-jerk reactions to specific events too often fail to see ourselves within broader systems of power, leaving many questions looming over the American umma: Where is our community’s prophetic voice? Our movement? Our critique? Our coalitions? Our demands?

American Muslims must therefore embark on a program of political education for ourselves and our community members in schools, mosques, living rooms, community centers, and conference rooms. We must create and join coalitions that are working to end mass incarceration, mass detention, economic inequality, and patriarchy in this country.

Groups like the Arab American Association of New York, Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), IMAN-Chicago, the Taleef Collective, and many others, have already started amazing work building a social justice movement in and outside Muslim communities.

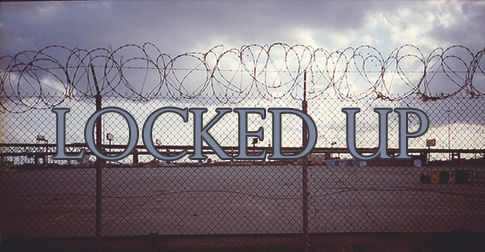

Mass Incarceration and the Caging of America

Laws like the Patriot Act reenacted a long history of discretionary powers and detailed systems of surveillance seen before in the War on Drugs and at the U.S.-Mexico border. And the recent scandal involving the NSA’s secret surveillance program has made Americans engage with an issue that had become a part of everyday life for American Muslim families after September 11th.

Racialized mass incarceration has resulted in cities where more than half of working-age African-American men are either under correctional control or branded felons and are thus subject to legalized discrimination upon leaving prison for the rest of their lives.

Under current trends, one in every three black males born today can expect to go to prison at some point in their life. One in every six Latino males and one in every 17 white males can expect the same result.

The War on Drugs and economic inequality are two of the primary drivers of this problem.

Drug offenses alone account for about two-thirds of the increase in the federal inmate population, and over half of the increase in the state prison population.

According to Human Rights Watch, people of color are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than whites, but they have drastically higher rate of arrests. African Americans comprise only 14 percent of regular drug users but are 37 percent of those arrested for drug offenses.

Civil rights advocate and writer Michelle Alexander frequently points out that there now are more African American adults under correctional control today than were enslaved in 1850.

Stop-and-frisk programs around the country also contribute to this trend. While suburban whites and middle and high income neighborhoods are not policed as heavily, this system, which activists have dubbed “The New Jim Crow,” targets low-income blacks and Latinos for minor drug offenses.

Another major reason for the growing prison population has been the increasing implementation of life sentences without parole (LWOP). This has been one of the most rapidly growing populations in the prison system. One out of nine prisoners in the United States is serving a life sentence.

The number of people sentenced to LWOP quadrupled nationwide between 1992 and 2012, from 12,453 to 49,081. In Louisiana, 143 people were serving LWOP sentences in 1970; the number had increased to 4,637 by 2012.

Of the prisoners serving LWOP for nonviolent offenses nationwide, 79 percent (2,577 prisoners) are serving LWOP for nonviolent drug offenses. Of the 2,074 federal prisoners serving LWOP for nonviolent offenses, 96 percent (1,989 prisoners) are serving LWOP for nonviolent drug offenses. Of the 1,204 state prisoners serving LWOP for nonviolent offenses, 49 percent (589 prisoners) are serving LWOP for nonviolent drug offenses.

Some anti-death penalty activists have advocated for life without parole as an alternative to capital punishment. But life without parole is essentially a sentence to die in prison. It is a slow form of the death penalty executed in a cage.

The United States is virtually alone in its willingness to sentence nonviolent offenders to die behind bars. It is among a minority of countries (20 percent) known to have LWOP sentences, while the vast majority of countries that do provide for LWOP sentences place stringent restrictions on when they can be issued and limit their use to crimes of murder.

In a global context, the United States is a major outlier in criminal justice matters–including on parole eligibility for lifers. There are 21 countries in the world, mostly in Latin America and Europe, where life sentences are unconstitutional. In an additional 25 countries, life without parole is unconstitutional. In Canada, lifers are reviewed for parole after 10-25 years. Last July, life without parole for non-violent sentences was ruled inhuman and degrading and a violation of human rights by the European Court of Human Rights. In the United Kingdom there are only 49 people serving LWOP who will all have their parole eligibility reviewed after a landmark decision. After the European Court’s landmark decision, all of these sentences will be revisited.

While crime rates have continued to drop nationally, the prison system continues to expand in many places while public education, social security, and other items that sustain our communities.

In cities like Philadelphia and Chicago, the criminal justice system continues to expand its reach over the lives of families of color as funding toward public education has been drastically cut over the past few years. As a result, public education has become largely a system reserved for only students of color and/or low-income backgrounds where students are funneled out of school and into prisons.

The failure of local, state, and federal policymakers to adequately fund and reform public education has created a “school-to-prison pipeline” which pushes public school students, especially our most at-risk children, out of classrooms and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems.

Recent data collected by the U.S. Department of Education continue to show significant racial disparities in school discipline, as African American students are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled compared to their white peers. Nationwide, 95% of out-of-school suspensions are for non-violent infractions –such as disrespect.

African American students comprise 15 percent of students in the collected data, but are 35 percent of the students who receive one suspension and nearly half of the students 44 percent who are suspended more than once. Over 50 percent of students in school related arrests or who are referred to law enforcement are black or Latino.

A publication by the Applied Research Center, a racial justice think tank, argued that institutionalized racism continues in this very manner in the 21st century. “Many students of color,” they wrote, “year after year, do not have access to fully credentialed teachers, high-quality curriculum materials and advanced courses.”

Many activists have proposed the following steps as part of a larger project in ending mass incarceration: 1) eliminate mandatory minimum sentencing, 2) decriminalize marijuana, 3) treat drug addiction as a public health issue, 4) end the death penalty and life without parole sentences, and 5) invest in sustainable communities by providing adequate jobs, education, housing, healthcare, and social services to poverty-stricken communities all across the United States.

Incarceration and public education are deeply connected issues affecting millions of people easily targeted by a system that increasingly does not exist to serve them. American Muslims should join or help build campaigns and coalitions in their cities dedicated to these issues in order to bring about profound structural social change in their communities and country.

Mass Detention, Mass Deportation, and Our Immigration Problem

hmed: I recently spent a week on the Arizona-Mexico border working with a non-profit named Border Links. Their primary aim was to expose us, an American delegation of graduate students, to the complexities surrounding immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border.

hmed: I recently spent a week on the Arizona-Mexico border working with a non-profit named Border Links. Their primary aim was to expose us, an American delegation of graduate students, to the complexities surrounding immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border.

Undocumented immigrants are being deported in record numbers causing some immigrant-rights activists to label President Obama the “Deporter-in-Chief.” Between 1892 and 1997, a total of 2.1 million people were deported from the United States. By 2014 President Obama will have deported over 2 million people–more than President George W. Bush and more in six years than the total number of people deported before between 1892 and 1997.

Most of the undocumented migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border are from impoverished rural areas harmed by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). After NAFTA, highly subsidized American corn flooded the Mexican market and displaced millions of rural farmers. Facing an inhospitable economic climate, these Mexican farmers followed flows of capital and exported themselves to the U.S.

Actual deportation numbers are at a record-high for two major reasons: 1) collaboration between local law enforcement and immigration officials and 2) militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. Through the former, undocumented immigrants who have any encounter with the police, say through stop-and-frisk or by running a red light, are subject to having their immigration status checked. If they are found without papers, they can be deported.

Many undocumented immigrants qualify for cancellation of removal if (1) they have resided in the U.S. for more than ten years, (2) they have “good moral character,” (3) they do not have a qualifying criminal bar, and (4) their departure would result in “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to the applicant’s spouse, parent, or child who is a United States citizen or legal permanent resident.

The Secure Communities project has rendered tens of thousands of undocumented immigrants guilty before trial causing them to go through the legal processes and wrangling involved with a cancellation of removal case. Undocumented immigrants not only have to find and pay for their own immigration attorneys, but are automatically given removal decisions without consideration of the four qualifying items for cancellation.

Some immigrant-rights groups have advocated passing comprehensive immigration reform as it stands in Congress. But many other activists and organizers see this piece of legislation as a step both forward and backward. Before American Muslims begin supporting this specific piece of legislation, we must understand what this “reform” means.

The bill includes a path-to-citizenship requiring that undocumented immigrants maintain continuous employment, earn an income above the federal poverty line, pay punitive fines, and be excluded from federal health care.

The Migrant Power Alliance in New York City released a statement rejecting the much-lauded Senate immigration reform bill. “These provisions fail to recognize,” the statement read, “contributions and the role that immigrants play in the U.S. economy, which keeps immigrants in precarious forms of employment and living below the poverty line in order to profit from their cheap labor.”

Most controversial is the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, requiring that the U.S. Border Patrol double in size from 20,000 to 40,000 agents. The Border Patrol will deploy Blackhawk attack helicopters, drones (the same drones used in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen). The amendment costs well over $40 billion, but the human cost will be greater. Deaths at the border increased 27% in 2012 due to ongoing militarization efforts, even as the rate of migration across the border is decreasing.

None of the immigration reform proposals have done anything to end or cut back mass detention. Comprehensive immigration reform would actually expand the criminalization in the immigration system. The current system operates on a quota, requiring that at least 34,000 people be detained every day. This figure would remain unchanged under the current Senate bill.

Furthermore, in order to apply for legal status, immigrants must have no criminal record. Many undocumented immigrants committed crimes due to their unlawful status and exposure to dire economic circumstances. This distinction, between “good immigrants” and “criminal immigrants,” not only obscures the root cause of crime, but also preserves the conditions that lead people to commit crimes by stigmatizing families and communities and denying them the opportunities to progress.

While on my study trip on the U.S.-Mexico Border, I began to see the effects of U.S. immigration policy and what might happen if comprehensive immigration reform, as it stands, passes. I met with a variety of individual and groups working on protecting immigrants and their rights, but three experiences gave me pause as an American Muslim.

The first was my interaction with various activists attempting to prevent deaths of the Sanctuary Movement. The Sanctuary Movement was a religious and political campaign that began in the early 1980s to provide sanctuary for Central American refugees fleeing civil conflict. While this was technically an illegal practice of civil disobedience, the movement was responding to what they saw as unjust federal immigration policies that made obtaining asylum difficult for Central Americans as well as the role the United States played in funding and arming anti-communist groups in Central America.

New Sanctuary Movements have sprung up in cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Boston dedicated to organizing congregations to fight mass deportation in the United States and provide sanctuary to undocumented immigrants.

Protestors lock themselves to wheels of deportation buses in protest of Operation Streamline.

Photo courtesy of Ndlon/Flickr.

The second was bearing witness to 80 dark-skinned men taking a collective plea bargain in one Arizona courtroom session through Operation Streamline, a “zero tolerance” border enforcement program that places undocumented border crossers into U.S. prisons. Streamline aims to criminalize all border-crossing activity, rendering non-violent second-time crossers into felons.

Over the course of an hour and a half, groups of five men accompanied by five lawyers stood before five microphones, where a script was read for them. They were asked if they understood the charges, the plea bargain and whether they had any concerns. The men had agreed to plead guilty to a lesser felony count in order to avoid up to twenty years in prison. Instead, they were deported, but not before serving between 30 and 180 days in prison as well as being handed a permanent record.

Although it was repeatedly stated that the lawyers explained the bargain they were agreeing to, it was hard to get a sense of how much the defendants knew. Nearly all of them agreed to the time-served without asking any questions. Only when one of the last ten individuals begged the judge for leniency – because he was only trying to cross to feed his children and support his family – did the rest of the defendants realize that they were able to say something other than “Si, si, si.” After that, every single defendant asked for mercy and were politely denied it.

The last experience that stuck with me was a conversation I had with an Ecuadorian migrant who had been thrown into immigration detention. He had come to America because his salary as a fruit seller no longer covered his son’s epilepsy medication. He was hoping to get refugee status – part of the reason he had come to America was because the local gangs had started to extort him for money and he could no longer afford what he once could. He had been in immigration detention since August.

However, unlike the individuals at Project Streamline, he was not entitled to a lawyer, as he was applying for refugee status. He too had epilepsy as a child, and he explained that he could barely understand or remember the things the judge had asked him for. “They need proof,” he had mentioned. But he did not know what that proof entailed.

He was constantly on the verge of tears. He rubbed his hands and picked at his nails. He barely smiled. It was difficult to watch. This was a man beaten down and confused by the system. He told us he would rather be deported and face his debt to the cartels than have to spend more time in detention, but his next court date was set for four months.

His only worry, like many parents of immigrants, was his child’s health and education.

These three experiences made me realize that a) the criminalization of dark-skinned male bodies is something that unites people of color, b) that the system around deporting and processing Latin American immigrants is incredibly large and unjust, and c) that Muslims have an ethical imperative to be involved in activism and debate on the Mexican border.

Moving Forward, Getting Mobilized

The rationale for both mass incarceration and mass deportation rests on the premise that they are needed to keep Americans safe from violence. As American Muslims, we have become accustomed to this fear-mongering rhetoric. This myth persists despite the fact that violent crimes in most parts of American society are at their lowest level in decades.

Both mass incarceration and mass deportation deliver some of their most destructive effects to the family members of the individuals imprisoned or detained who find themselves denied parents, partners, and vital economic support despite having broken no laws themselves. They are twinned forms of surveillance that operate on poor brown and black masses, rather than individuals. This surveillance creates an environment where people must move through life in perpetual fear of police or immigration enforcement officers.

To truly build a safer world, we must address structures of poverty and inequality that lead to crime. Genuine and long-lasting community security can only be achieved by investing in education, employment, and health care for all people. In this vein, we must continue the unfinished work of Dr. Martin Luther King, who said:

“The struggle today is much more difficult. It’s more difficult today because we are struggling now for genuine equality. It’s much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job. It’s much easier to guarantee the right to vote than it is to guarantee the right to live in sanitary, decent housing conditions. It is much easier to integrate a public park than it is to make genuine, quality, integrated education a reality. And so today we are struggling for something which says we demand genuine equality.”

We call on American Muslims to move beyond keyboard activism and turn instead to focus their energy and political work on building and mobilizing their communities on specific political issues; educating their mosques about mass incarceration, detention, and deportation; demanding that policymakers adequately address public education, health care, poverty, and employment; and dreaming of a world where millions of people don’t have to live behind bars and inside cages.

Waleed Shahid is a freelance writer living in Philadelphia. Other than reading and writing as much as he can, he is currently working on two major projects: starting an arts and social justice summer camp for American Muslim youth and Decarcerate PA, a grassroots coalition seeking to end mass incarceration in the state of Pennsylvania.

Ahmed Ali Akbar is a graduate student in Islamic Studies at Harvard Divinity School, a writer, and the editor of Rad Brown Dads. His interests include race, class, and Muslim American art and culture.

Featured image courtesy of Michael Cramer/Flickr.