One-way ticket to hell

I woke up to a crumpled piece of paper someone had placed next to my head on the pillow. Tiptoeing to the bathroom and using my mobile phone as a torch, I tried to read the shred of paper that looked like it had been torn hurriedly from the daily news. It was a picture taken in Syria. Some armed men had just thrown a headless corpse over a bridge into a river. The body was airborne. Arms and legs were spread out, all pointing in unnatural directions as if broken and uncontrolled by joints, sinew and muscles. One of the men was kneeling with his hands held aloft, his face toward the sky, his mouth open, passionately mouthing something unheard. The ground around them was drenched with dark blood and debris. On the back of the picture was a little note written in thick black marker: “One way ticket to hell! Please don’t go! You are nuts!”

The message was clear, and it was not the first message of this kind either.

In the summer of 2012, I had been lingering in Lebanon for more than three weeks, unable to decide where to go next in my quest to understand the Middle East in greater depth than the mainstream media allowed me. I was following a one-year personal journey to trace the path of Islam from where it began. According to Islamic history, my next destination should have been Syria. However, the war there was getting uglier each day, and friends were doing everything possible to sabotage my plans and prevent me from crossing the border. They even staged a funeral using a symbolic coffin, as they expected that I would be butchered or blown up.

My roommate Francesca was an Italian freelancer, who, like many other journalists at the time, was in Lebanon trying to cross the border to Syria illegally. Her most probable chance would be through connections with rebels who would guide them into Syria through the northern mountains close to Tripoli, for a fee. At first, I was madly attracted to the idea, until I found out how much I would have to pay and how dangerous the crossing would be. The government’s army was reportedly indiscriminately bombing the area and the northern border was heavily mined. I decided that discretion was the better part of valor and abandoned the idea. I left Francesca alone with her risky plan since I wanted to actually get into Syria, rather than perish on the border. In the end, I decided to take my passport to check with customs about the situation in Syria, and to see whether the whole plan of getting into the country would turn out to be a mission impossible.

At the customs post, I played dumb and innocent. I said I was a tourist in Beirut and well, since Damascus was so close, I just wanted to see if I could have a quick visit to this beautiful city with a visa on arrival.

“You are not a journalist, are you?”

“No!” I answered. My heart was thumping. I stole a quick look at the custom official’s computer screen. A senior officer came behind him and it was quite obvious they were Googling my name. The evening before, I had edited all personal profiles on my blog, LinkedIn and Facebook. I had deleted everything that could be traced to my journalistic past. Yet I felt like they were going to put me through a lie detector.

“Madam! You can just pay the fee and enter Syria. Please bring your passport to the head office at the corner for the stamp.”

W-H-A-T? For a few seconds, I just stared at the young officer. He kept smiling. I looked over my shoulder: A small handbag with my camera and $400. I looked at my feet: A pair of worn out flip-flops. I looked across the hall at the two Syrian girls who shared the taxi with me: They were clapping their hands and signaling me an invitation to stay the night at their family’s house. I cursed myself as I realized I was wearing contact lenses and didn’t bring any solution with me. I closed my eyes and in my head, the picture that was left on my pillow in Beirut reappeared, floating: The headless body with its broken limbs and hot blood squirting in all directions.

“Assad OK”

The highway connecting the Lebanese border and Damascus was beautiful and smooth like a thread of silk, completely different from news that the government was seeding border towns with mines. The two Syrian girls — Dana and Amira — and I arrived in Damascus at around 9 p.m. It was hard not to be fascinated by the busy streets, crowded shops and cheerfulness of the people walking around. Many girls were not wearing headscarves and some of the teenagers showed off very sexy miniskirts. As I took photos, Dana and her sister exchanged looks. They later told me to delete everything: “Shurta! Shurta!” (Police! Police) they said, crossing their wrists, as if locked in invisible handcuffs.

When we arrived to their house, my host family of 10 people was sitting on big thick pillows lined neatly against the wall of the living room. They gave me a corner near a large rudimentary heater. Food was served while everyone was half entertaining me and half watching TV. On the screen, Homs was being bombed. Walls and buildings collapsed after each other like houses of cards, sending up curtains of fire and filling the TV screen with whirling black smoke. The father turned to me and shook his head: “Assad is bad! He is destroying the country! I want him dead!” He then stood up, pulled down the cabinet, grabbed three passports and showed me many visas to England during his career as an engineer. He then asked me if I could sponsor him or invite him to Holland. The whole family was silent and stared at me. Dana stopped eating. In the dim light of the room, I could see the flickering TV screen in their eyes full of hope. My heart ached as I apologetically explained to them that it would be an impossible task.

Building destroyed by Syrian forces in Homs >Flickr/H.usa

That night, I placed my contact lenses under my tongue to keep them moist and went to bed, a trick Francesca had taught me, though I doubted that she herself had ever tried. The girls and I lay neatly on three mattresses. It was after midnight and we suddenly heard a gunshot far down the street. I froze inside my blanket. Dana reached out and took my hand, and in her sleepy voice told me not to worry: “Just some aimless fire.” I squeezed her hand, staring into the inky darkness. I was not sure if she was telling the truth or just soothing the anxiety of a poor chicken-hearted tourist.

The next morning, I entered the living room while everybody was having a fierce discussion. I sat down next to them on the pillows. I heard the name of the Syrian president. I heard … my name. I heard lots of sifara (embassy). I could vaguely guess that they were continuing the talk of yesterday, which obviously involved me. Failing to understand the conversation, I began to play around on the screen of my phone. When I put it down, I realized I could feel a burning gaze. I looked up and saw Abdul — Dana’s 9-year-old brother. He stood there, drilling his eyes into mine with fury. He then jumped to his mother, pointing at me and screeched hysterically like a siren: “She is recording! She is recording! She is a spy from Assad.”

Abdul’s mother quickly covered his mouth. She looked at me while I clumsily showed her a music app. I silently cursed myself, expecting to be kicked out of the house. But Abdul’s mother looked at the running title of an Arabic song across the phone’s screen and decided I was innocent. She told Abdul to sit in the corner with his father. He complied, but his angry face made it very clear that not a hair on his head believed a single word I said. To get me out of the awkward situation, Dana motioned for her brother and me to move to another room.

“We like Assad you know,” Dana told me. “Assad is OK! The president is OK!”

As we sat down on the mattress, Dana grabbed my shoulder. Her huge eyes were filled with fear and confusion: “Assad OK!” Her brother dropped himself heavily on the couch. I heard him snort loudly and mumble to himself: “It is not true.”

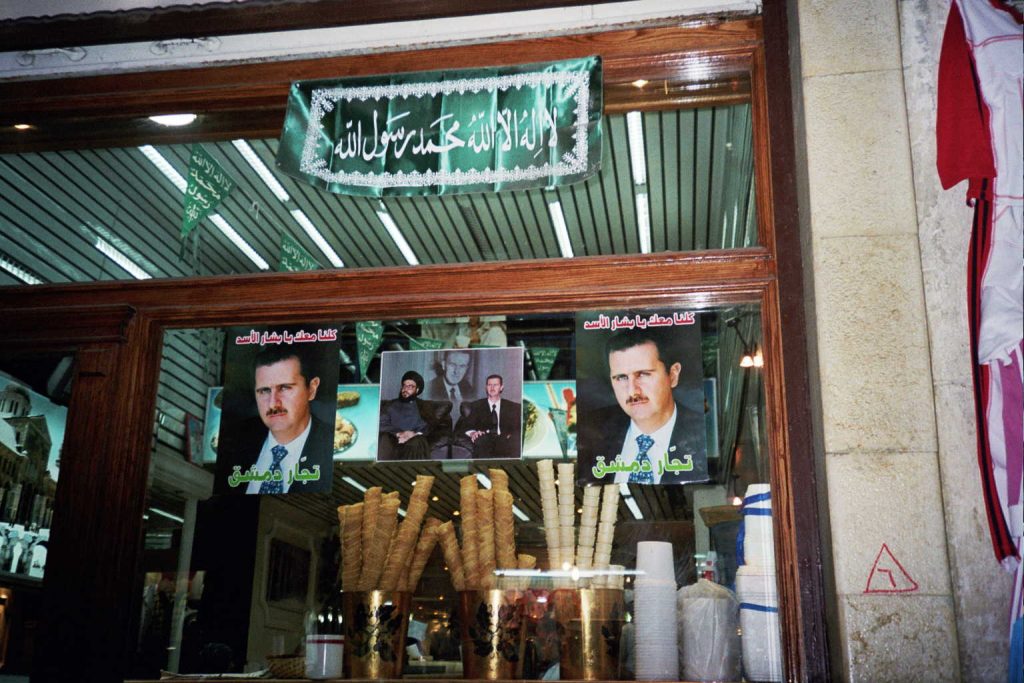

The fear and split I witnessed in this family was not uncommon. Families are torn apart over a civil war that is too complex and disastrous. There are more than 1,000 opposition groups among fewer than 100,000 rebels, nearly half are jihadists and hardline Islamists such as Al-Qaeda and Nusra, with a very small fraction of secularists and nationalists. Islamic State was then not yet in the picture. There are also a considerable number of Syrians who showed obvious support for the dictator, something that media failed to cover during the initial stage of the conflict. All over Damascus during those days of May 2012, shops that displayed Assad’s picture on their doors, windows and balconies dotted the streets and were scattered around the main squares. Many shop owners received threats as regular customers refused to come, revenue dropped and businesses went bankrupt. But there they were still, public and proud, the photos and posters of Assad with the Syrian flag in the background. I was overwhelmed by the observation that a large portion of the population genuinely backed Assad. They were not just Alawites in the armed forces, but also an elite centered around the merchant classes of Aleppo and Damascus who are mostly Sunnis, the upper middle and middle class that enjoys social benefits and economic advantages, Christian and Druze who count for almost 20% of the population, and last but not least, many educated women who have been enjoying a more liberal and equal stand in public life under a secular government.

Photos of Assad outside of an ice cream parlor >Flickr/upyernoz

From Syria, with Love

At the moment of this writing, the catastrophe in Syria was mounting with over 470,000 people killed, and more than 5 million refugees. The war has rolled on since 2011, punctuated by chemical weapons, scud missiles, war planes, foreign jihadists and the rise of the Islamic State.

Yet, on my very first day in Syria, I was invited to stay with and cared for by a family of complete strangers. The second day, they carefully arranged escorts to make sure I was “transferred” safely to my next host family. I did not know this family either. They had accepted hosting me as a favor for a mutual friend, who had agreed to receive me but had to suddenly flee Syria. Noura, a 18-year-old university student studying chemistry who looked extremely Scandinavian with huge green eyes and flowing blonde hair, picked me up. I thought a wealthy Christian expat family would be hosting me. I was wrong. Noura’s family is Muslim, and her mother wore a hijab. They were refugees themselves from Homs, and had just barely escaped and arrived in Damascus a few days earlier. Yet, they agreed to welcome me into their newly rented tiny flat. Noura and her family are among 7 million displaced people inside Syria, many of whom have no support.

“Everything was destroyed and we had to pay so much money to hire someone who dared to drive us out of the city [Homs]. All the way, we had to lie down inside the car, it was hit several times but luckily no snipers caught us. We had to leave our internet cafe behind and now we have to rely on the money from our father and other relatives,” Noura told me.

The anxiety was obvious in her mother’s sorrowful and worried eyes, although whenever caught my gaze, she smiled. The single mother of two teenagers (Noura has a 15-year-old brother) kept apologizing for their home’s simplicity. She would still shake from their ordeal and cried every night. I often went to bed when the three of them were cuddling on the sofa, watching endless Turkish soap operas until morning. It was a habit they found hard to change. In Homs, their internet cafe was always open until the last customer left. No matter how late they went to bed, I always woke up with breakfast on the table: tea, boiled eggs, bread and zaatar, a delicious herbal blend that includes sesame seeds and dried sumac.

I didn’t know I had been cared for with every last bit of their money until that evening when I saw Noura and Jamal crawling on the floor looking for something under the couch: “I lost some notes,” said Noura. “We need that for Jamal’s taxi tomorrow so he could go to the interview.” Jamal was preparing to apply for a high school scholarship in the United States.

We found the notes, but realized it was not enough. How about food? How about the taxi or bus on the way back? How about tomorrow?

“My father promised to send us some money this afternoon,” said Noura softly as she quickly glanced at her mother’s room. I could hear Samah’s sobbing from behind the door. For a prestigious family in Homs, this situation must be uneasy for her, waiting for money from the divorced husband.

I tried to give Noura what I had left from the $400 cash I brought to Syria but she refused, only taking a few dozen dollars for Jamal.

“Take more, please!” I insisted.

“No!” Noura was both angry and embarrassed. She gave the money to Jamal and noted the amount down on a piece of paper.

Two days later, Noura’s mother returned me the money. She apologized, quoting that guests were gifts from God and they were sorry I did not receive what I deserved.

Next to the war

Before arriving in Damascus, I was told to stay in the old quarter where cars could not enter to minimize the chances of being hurt or killed by car bombs. After settling down, I was often teased by a Czech journalist I met here that if I wanted to get killed by a car bomb, I would have to try much harder. A car bomb is expensive and it would normally be reserved for carefully targeted high-ranking officers, not a useless irrelevant Asian loner like me.

What truly surprised me was the difference between day-to-day life and what I had expected to see. It was deep into the uprising, yet, the streets were lively: Women still relaxed outside the mosque as they smoked their cigarettes under the trees, shisha smoke floated from the cafes, the bars rocked deep into the night, couples held hands walking down the street, young girls happily picked up their goodies around mannequins being dressed up in embarrassingly sexy lingerie that lined the busy Al-Hamidyah souk, and elites still had pool parties while the skyline burned. Symbols of everyday normality included the deafening wedding drum over the weekend. As a single woman, I felt safe to get back home at 4 a.m. and find the internet shops still open. In fact, after months of traveling in the Middle East, from ancient Yemen to ultra-modern Dubai and the heart of the region’s youth scene in Beirut, it was only in Syria I had no problem with internet connection and access to Facebook, Twitter and Skype.

However, in the media, Syria was on fire. YouTube was filled with bloody executions, Twitter with bombings, the TV screen was all smoky with reports of war and the radio crackled with shooting. It was hard to make sense of the difference, but both the seemingly normal appearance of life in some parts of the country and the bloodshed are patterns of the big picture. Life has to move on. People can’t sit down and moan day after day. They had to brush the dark side of reality aside, even as a sort of self-protection. A local told me: “As long as I can smoke shisha every afternoon at 4 o’clock with my old friends in the café downtown, I know things will be just fine.” A Frontline report on October 27, 2015 shows exactly that: Syria is torn by the war, but retains some shreds of superficial normality and desperate optimism with fashion shows, classical concerts and even tourism festivals.

I experienced this uneasy match of reality through a night out that featured the full speed of bustling life in Damascus. Noura and I joined a local youngster party at 2:20 a.m. in the bar Marmal, which local youths said was one of the hottest nightclubs in Damascus. The boys were charged 1,000 lira ($15) with coupons for four free drinks, the girls got in for half price with as many drinks. We ordered shots, poured down at once together. The DJ hit on with a mix of chart music and Arabian belly dance music. Some guys danced along the top of the bar followed by the bartender who showered the writhing mouth-wide-open crowd below with whiskey splashing from the bottle in his hand.

Amid this hedonistic scene, a local guy in our group got a message on Facebook: a YouTube clip of a rebel being buried alive by Assad’s soldiers. The unfortunate guy cried “Allahu Akbar!” (God is great) as the last shovels of dirt covered the top of his head. “Fuck Assad! Fuck Assad!” The reveler shook his head furiously and pressed the “share” button. In just one click, 637 of his friends were updated with the gruesome video. Putting his phone back in his pocket, he turned to me and cheerfully winked: “Another shot?”

The juxtaposition of youthful normality and abject horror so recently visited upon Syria left me struggling to get my bearings.

So, of course, not a single friend believed I was safe and sound in Syria. When they saw my Facebook post of Noura and me visiting a Damascus mosque, the optimists back home thought my Photoshop skills had improved, while the pessimists wondered if I was posting under the control of secret service.

A people’s court case

My time in Syria did bring personal risks.

Like the day I was walking back to the city from a shrine at Qassioun Mountain, where two sons of Adam, Kabil (Cane) killed Habil (Abel) because one could marry his beautiful sister and the other could not. I was talking to two young boys who also visited the shrine. I told them how proud I was because I had just touched the hand print formation on the rock ceiling in the mountain cave. This hand print was said to be of angel Gabriel – the messenger of God, the angel who dictated the text of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad.

The boys were interested in my stories. Taime was from Lebanon and had been working for a few years in Damascus. He looked very fashionable with a pony tail and leather jacket, very much stereotype of someone from trendy Beirut. His friend Zaid looked more like a nerd with a pair of glasses and delicate smile. As we entered the Old City quarter and passed a beautiful abandoned old house, they offered to take a picture for me. Thinking it would be a nice shot for Facebook, I agreed and started to climb over the pile of debris at the entrance. When I turned around, all I could see was the pony tail of Taime disappearing behind the corner. With my phone and my bag.

Qassioun Mountain at dusk >Flickr/Thomas Stellmach

The few seconds it took me to realize that I had been robbed felt like ages.

I ran after Taime screaming at the top of my lungs. Flashes of despair hit my swirling head as I remembered that not just my camcorder was inside the bag, but also my passport. I had to bring it along for the military checkpoint on the way to the mountain. After a few corners, fear hit me as I could not run anymore and Taime was getting away along the zigzag narrow alleys of the Old Quarter. I collapsed. I couldn’t breathe. I could not scream anymore.

Taime turned into the main alleyway of Bab Touma and was caught by the locals. They started to attack him. Someone helped me to stand. I was panting furiously. I was given his wallet and realized that my smartphone and my bag were with Zaid, not Taime. Shaking all over, I managed to take his ID from the wallet and stuffed it inside my bra. I was shaking so badly I could not hold anything. Someone brought a glass of lemon juice and helped me to sip it slowly.

The locals brought Taime to a house where about 20 men sat in a courtyard and started to investigate the problem. Tea was served. And Taime was placed in the middle of the circle. More and more people came in, looked at him, talked and discussed. Some left and some others arrived. It was a huge event in the neighborhood and it seemed like everyone wanted to be a part of it.

While waiting for Zaid to be found, Taime was being terribly humiliated by the local men. They first wanted him to kneel down, then to kiss my hand, kiss my feet. They searched his whole body and threw nasty comments about him. Then they grabbed a pair of scissors and asked for my permission to cut his pony tail. I was overwhelmed with the humiliation and tried to stop them. But before they considered my request, one man said that Taime was probably gay since he had long hair and wore a sleeveless top inside his leather jacket. There was a dead silence as Taime was taken to a corner so a man could check him out. I tried not to look.

When they came back, the men started to take his mugshot pictures. They laughed that this resembled the registration process of newly arrived prisoners in Western movies. He was then forced to apologize to me. He did not look at me, and with his head down, he told me that they never intended to rob me until he and Zaid saw my smartphone. It was just such a beautiful thing and they could not help it.

I felt angry, guilty and helpless all at the same time. I hated this man for what he did to me. I hated the cheering men around me for humiliating him so badly. I also hated myself for being so mindless toward his life. Taime worked in tourism and since there had been virtually no tourists lately, he was obviously having a hard time making ends meet. The boy is smart, just not smart enough to resist a fancy smartphone.

After Zaid was caught and my bag was returned to me intact, I told the men that I wanted to report the two to the police. They discussed this request and suggested that I not do so. They did not trust the police and they were not sure what kind of pictures and videos I had shot, which could cause me unwanted troubles. Further, Taime had already been well punished. If he was brought to the police, he could end up in prison for a few years. They felt that Taime deserved a second chance.

I finished my eventful day by walking with John, who had been helping me with translation, back to his workplace. He was a bartender in Club 7/11, where he was supposed to have opened the door an hour ago. I called his boss and asked permission for John to stay a bit longer to help me with tricky conversations about street justice. His boss reluctantly agreed. When we got to the club, I realized I was meeting the biggest jerk of all time. This man barked at John, not listening to one word I said. “She is not your friend! Why are you doing this? You are responsible for this bar, not her!” Turning to me, he said: “Yes, this is what people in our culture do! We help people and we sacrifice a bit of ourselves. And when you are back home, you will tell your people about your mugging and not the help that was given.”

I felt a burning animosity toward him for his lack of understanding of my openness to his country and people who had been so good to me. John later told me that his boss had returned to Damascus after 10 years in the U.S. and “also brought back his fucking American heartless mentality. … I have no idea why his bar is jam-packed every night. … Why is it that bad people can make good money?”

Basel is a Kurd

After two weeks, I decided not to burden Noura’s family anymore and went to check in at a beautiful hotel in the old center. Passing a small entrance, I could see through the dwelling that through its bow window looked out onto a grand, beautiful vineyard and garden. The crisis had forced many hotels to change their business to a cafe and a restaurant to make ends meets. This splendid 600-year-old house transformed from being an excellent youth hostel to a shisha-smoking corner cafe for middle-class locals. I was, of course, the only guest and I was allowed to choose from any of the 20 available rooms, all made up in anticipation of a return to normality.

With dreamy eyes, Basel, the manager, often recalled the happy days when all the rooms were packed and when he was surrounded by beautiful traveling girls from all corners of the world. When I told him that a grand hotel had offered to accommodate me for only $50 a night in the very same room that had hosted Angelina Jolie, he sighed heavily and said: “Mai, you can stay in our hostel for free then! I just want you here so that I can at least hope that tourists do still exist on this planet.”

I declined his offer, reflecting on the economic principle of supply and demand, distorted in a war zone.

One day, when Basel gave me a lift to the city, we passed a beautiful memorial of Saladin. He glanced at the statue that featured the most powerful and admirable Muslim military leader of the Crusades, mounted on a fearsome warhorse. Basel bit his lip and mumbled, “He could have freed us from all of this pain!”

My heart ached a little for this young generous man caught up in this fate of history.

Basel was a Kurd.

And so was Saladin — the powerful sultan who ruled a vast territory in the Middle East during the 12th century. Legends have depicted him favorably. His enemies, the Crusaders, called him the Flower of Islam, an unusual complimentary sobriquet for an enemy. He was admired by Muslim followers and Christian foes. His knightly virtues are often compared with those of England’s King Richard the Lionheart. For two years, both were involved in almost daily combat in their attempts to recapture and occupy Jerusalem. When Richard fell sick, Saladin sent him a gift of the choicest fruits and delicacies. On another occasion, when Richard’s horse had been killed in a battle, a fine Arabian steed was sent as a replacement. Richard was said to have wanted Saladin’s brother to marry his sister, and Jerusalem would be their wedding gift. It was said that Saladin’s courtesy in honorable warfare had inspired the European code of chivalry.

Statue of Saladin >Flickr/Sean Long

But Basel talked about his powerful ancient ethnic ancestor with a twisted dilemma.

“He fought for the unification of Muslims, and now his own people have ended up being stateless!”

Nobody knew that Basel was a Kurd. Nobody knows exactly how many Kurds there are in the Middle East because none of the countries where they live want to acknowledge that the Kurds even exist, let alone count them. Unfortunately, Saladin, the Muslim Unifier, could not foresee how his homeland Kurdistan would “became a fateful experiment, exposing the fault lines of a world gone mad.” The 25 million Kurds are the world’s biggest and one of the longest-surviving ethnic groups without a country (David McDowall, A Modern History of the Kurds).

After WWI, the British and French redrew the lines of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. The British promised the Kurds their own state, Kurdistan, if they revolted against the Turks. However, they betrayed the Kurds and divided Kurdistan in a way that would spread the Kurds across five unwelcoming countries: Turkey, Armenia, Syria, Iraq and Iran. To make the matters worse, Kurdistan marks the frontier among the countries that either hate or distrust each other: between the Soviet Union and NATO, between the Gulf states of Sunni Islam and Iran of Shia Islam, and between the U.S.’ staunchest allies and worst enemy. The Kurds have been fighting for a dream that no country wants to come true.

In 1962, in a special census designed only for the Syrian province of Jazira where Kurds lived, 120,000 Kurds were stripped of their citizenship on the grounds that they were actually refugees from Turkey. Basel told me that the government gave them only one day to register and to hand in their ID card for “renewal.” Many could not make it on time, and many were informed that they were not Syrian anymore and were being registered as ajanib, or foreigners, with no ID card. Basel and his family belonged to half a million Kurds stateless in their homeland.

Being a Kurd has never been easy. Officially, they are not allowed to speak their own language, register their children with Kurdish names and start businesses that do not have Arabic names. The Kurds have been looked down on as either backward peasants or belonging to a servant class. In Arabic idiom, anyone shabbily turned out is “dressed like a Kurd.”

A few years ago, Basel moved to Damascus. Without an ID card, he spent a fortune on bribes to settle down with good papers. For Basel, it is a dark joke that the land where the statue of Saladin — a Muslim for all Muslims — stands so proudly, should also be the land where his successors have endured persecution, betrayal and flight from terror.

The sadness runs much deeper than the loss of dignity on the battlefield. With his death, the spirit of Saladin has long disappeared and so has any idea of chivalrous warfare. Long gone are the days when wedding parties were saved from attack. Instead there is indiscriminate bombing from afar. Long gone are the days when rival military leaders of two different religions would send each other food when one fell sick. Instead it is sectarian war where enemies would film how they cut out and ate the organs of each other. The warriors of a thousand years ago seem more civilized and humane in their conduct of conflict than the warlords of the 21st century.

“Saladin must be turning in his grave!” Basel said after another long silence. “Many Kurds hate him, for he put Islam first and Kurdistan second.”

I looked at Basel’s deep green eyes and thought I was looking at the saddest Syrian among those who were not physically attacked by the war.

I was wrong.

Victims and demons — victimized and demonized

After the third week, I decided to fly to Aleppo, a city in the north and a rival with Damascus to be recognized as the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world.

Hani, a regular couch surfer host, was more than happy to offer me accommodation. He had been jobless for several months and his couch had been unoccupied for more than a year because of the unrest. As a true hospitable Middle Eastern host, I was given his bedroom and he moved to the living room couch. When I met him, he looked so different from his online profile picture. After only a few months of being jobless, he transformed from a cheerful muscly sun-tanned beach boy to a bearded depressed-looking man with an expanding belly.

Hani is an Alawite. There are approximately 2 million of them in Syria. Many Muslims don’t consider them decent Muslims. But the president is Alawite and most of his army is made up of Alawites. To a certain extent, the war in Syria could be seen as a sectarian war between Alawites and Sunni Muslims.

Alawism is extremely secretive. Alawites’ holy books and rituals are restricted to only a few believers who are carefully chosen. Although the sect split from the main branch of Shia Islam, the whole religion is actually a mysterious cocktail of Islam, Christianity, Neo-Platonism, Gnosticism and Zoroastrianism with several other belief systems such as Phoenician paganism, Mazdakism and Manicheanism thrown in for good measure. Amongst this rich cocktail of beliefs and ‘isms, Christianity is the most obvious. Some have even accused Alawism of being a secret Christian proclivity because it has a trinity, celebrates some Christian holidays and honors many Christian saints. On top of that, alcohol is permitted; wine represents God and plays a sacred role. Pilgrimage to Mecca is seen as a form of idol worship, and Alawite women do not normally wear a veil or headscarf.

The obsessive secrecy of Alawites — together with unveiled women, night-time ceremonies and wine-drinking rituals — have long been sources of suspicion that Alawites have been hiding bizarre sexual habits. Like Hani, many Alawites are not sure how to explain or justify their practices, mainly because of their religion’s secretive nature. When Hani was small, his Muslim teachers would tell students that Alawites forced sisters and brothers to sleep together, and that they all have tails. “Help! I don’t have a tail, this means I am not Alawite!” Hani remembered running home crying, deeply scared because he did not have the “proof” of being Alawite.

In another example of how anti-Alawite sentiment became embedded in his life, Hani’s grandmother used to ask him: “Why are you in such a hurry? It’s as if you are rushing to kill Alawites in the souk!” It’s a saying based on the historical hatred for Alawites.

What would you do if you were under this threat of persecution? Alawites have a solution: A chameleon-like capacity to change their practices in a manner that aids their survival in the face of less flexible customs. They sought an affinity with Christianity to gain sympathy from France when Syria came under its mandate, and they were willing to adopt Sunni practices to be more accepted in a Sunni-majority country. In short, like other sects of Shia origins, Alawites practice taqiya (religious dissimulation), which allows them to lie about their religion or imitate practices and pretend to be part of other religions to be accepted and avoid persecution.

Being powerless is not an easy feeling, and intentional neglect seems to be a silently approved mechanism of self-defense.

This mindset explains very well why Assad’s regime has been successful in encouraging Alawites to act like the majority Sunni, to pray like Sunnis and even dress like Sunnis. In many ways, Alawites have sacrificed their religious character in exchange for social stability and a share of political power.

There is one problem with this blend-into-the-background chameleon tactic: Alawites were never supposed to be linked with the ruling elite and thereby expose themselves. A chameleon is forever destined to blend in with the background, silent and camouflaged from threat. Its survival depends on its patience and avoidance of a loud, vivid, specific identity. Needless to say, this was impossible in Syria where no matter how much ordinary Alawites tried to assimilate, there would be always a group of ruling Alawites who stood out, for good and bad.

Our chameleon has donned an orange hazard jacket complete with reflective stripes.

Now at the age of 32, Hani was experiencing deja vu as he witnessed Alawites being demonized in the escalating civil war between the Alawite-led army and the Sunni-led opposition. In 2011, Hani was part of the Arab Spring, during which young liberal secularists, regardless of religious background, demanded regime reform and democracy. “It is over! It is dead!” he said. “Now it is all about Alawite versus Sunni.” Islamist rebels once clearly declared: “Every Alawite killed is one Alawite killed because of Assad.”

The division is evident everywhere. Recently, Hani took a taxi home with a friend and the driver was telling him that he wanted to kill all Alawites. Hani was not so brave but his friend actually gave out a lighter: “I am Alawite. Now you can burn me alive bro!” On a more recent occasion, when Hani was on his way to pick me up, a neighbor suddenly asked him if he was Alawite: “I said yes, knowing that it was the beginning of my end. Now a bullet can be in my head anytime!”

I looked around and realized that Hani’s apartment looked more like a cage. It was closed up: The windows were shut, sealed and nailed. A cold shiver went along my spine.

Having gained more than 30 kilograms since he lost his job, he now lived like a fat, scared mouse in this prison of his own. That afternoon, he tried to call his three sisters in Homs who had not stepped outdoors for months. In May 2012, Homs was still being bombarded and was a no-go zone. But despite the privations, I heard a girl’s voice at the other end of the line. She sounded cheerful. I later learned that Hani’s sister was pregnant with twin boys and she was very excited thinking about what she would name the babies. A sharply contrasting ray of sunshine in an otherwise endlessly bleak outlook caused me to reflect that life does go on, somehow.

“I talked with my brother in-law the other day and he was not at all worried about the names of his sons,” Hani smiled at me sarcastically. “He said he would just name them after any two of his friends who were killed that day by the opposition.”

Hani showed me his picture. He was a wall of a man, almost 2 meters tall, who served in the Syrian police force. He belonged to one of those, who according to the opposition’s narratives in Aleppo, were believed to be capable of killing civilians solely because he is one of Assad’s men.

Hani explained that one day, this massive guy hysterically broke down in tears confessing to Hani that he peed his pants every day. He reported that many Alawite girls had been kidnapped and raped by armed opposition gangs and that he lived with the guilt of being an accomplice. Several fatwas had been issued to make rape against non-Sunni women legal. These women were named melk al-yamin, a reference to non-Muslim sex slaves. Worse, there had been cases of Alawite girls being killed by their own fathers for fear of being captured by rebels, in which case the victim would then become war booty. A girl Hani knew was strangled to death in her father’s arms while the opposition surrounded their house and the father could hear the soldiers rushing up the stairs.

Syrian girls, carrying school bags provided by UNICEF on their way to school >Flickr/Jordi Bernabeu Farrús

On the second day of my stay with Hani, someone knocked on his door. Hani and I froze. The individual knocked a few more times before we could hear footsteps fading down the wooden stairs. After a few minutes, Hani opened the door carefully and peeked out. “It is better to keep a low profile these days,” he said simply.

“But then who are you supporting now?” I asked Hani before leaving Aleppo.

“No one! I hate the president! But I also do not see in what way this civil war can lead to any solution!”

“If a gun is put to your head, and you had to choose…”

“Well!” Hani exhaled. “I would throw Assad in the bin if I had a better choice. But between him and the Sunni Islamist opposition, gun to my head, I would go for the lesser of the two evils: Assad.”

The most recent news I have received from my friends in Syria is that the famous Alawite adaptability has taken to capitalism. With Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the West funneling money and arms to the Syrian opposition, some Christian rebels were said to shout “Allahu Akbar!” to the camera and present themselves as Sunni fighters to the oil-rich patrons.

“They would memorize the whole Quran if they have to, as long as the money from Saudi keeps coming to allow them to buy more grenades and AKs.” It seems that in a dire situation like Syria at this time, not just Alawites, but everyone is learning chameleon tactics.

As the war rolls on

I returned to the safety of Europe after almost two months in Syria, where the war escalated quickly. Hundreds of people died each day, cities and villages crumbled into dust. However, the human mind has evolved a mechanism to cope with problems that can’t be solved: We ignore them. Many of my friends became wary of me and began to shut me down, politely but decidedly, if I ever mentioned Syria. Not that they were unkind or unconcerned, but it was because they didn’t know how to deal with the pain. Being powerless is not an easy feeling, and intentional neglect seems to be a silently approved mechanism of self-defense.

Then Syria became more than just news in the media with a sudden influx of refugees to Europe. Since the war began, around 7 million people are displaced inside the country, more than 5 million have been forced out of their homeland to live either on the streets or in simple and basic refugee camps in Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon. In Lebanon, there is one refugee for every four Lebanese. However, it was hardly top news. Syrian refugees became the focus of a heated debate when they mingled with millions of other asylum seekers in making one of the most dangerous journeys to get to Europe by crossing the high sea of the Mediterranean, or walking for weeks on end through hostile European countries that decidedly did not want this migrant influx.

As most of my Syrian friends are active on Facebook, I have been able to keep track of their efforts to survive. In 2014, Basel fled to Lebanon and revealed that he was gay. Lebanon and its famed reputation for leniency and tolerance toward the LGBT community offers him an ideal refuge. He, however, was not comfortable with telling everyone he was a Kurd, since some of his friends in the LGBT scenes in Beirut are of Turkish origin and do not support the Kurdish separatist movement in Turkey. Meanwhile, he considered going to Iraq to join the Kurdish army, which has been gaining the salute of the world for fighting IS fearlessly. In Syria, Kurds are forming a strong opposition force and hoping to gain independence.

Shockwave from a tank firing in Aleppo >Flickr/El Gee Cafe

When the Americans invaded and overthrew Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraqi Kurds seized three northern oil-rich provinces, set up a parliament, established a capital at Erbil and mobilized a formidable militia, the Peshmerga. Over the past decade, the Iraqi Kurdish region has gone from one of the poorest to one of the most affluent areas, flourished by energy sales to Turkey and Iran. Basel has been stateless since childhood and is drawn to the idea of social and ethnic belonging. However, I often sense that he is torn between two identities that seem to exclude each other: being a Muslim Kurd and being a Muslim gay. It is clear that Basel has found a new home for his persona as a homosexual in Beirut, but his heart is split and his mind never rests.

Noura and her family have been the luckiest of all the Syrians I know. Noura and her brother Jamal had been trying to apply for a scholarship in the U.S. where their oldest sister was a university student. Jamal was a very shy boy, very attached to his mother and often curled up to sleep every night next to her. When I was in Damascus, I offered him a long session of interview practice filmed on camera. We played the video back several times and I could see that the boy was totally taken by surprise by how reserved he looked on screen. Noura once came to my hotel at midnight with her laptop so I could help her with writing a cover letter. She was clueless on what to write for her scholarship essay. “What is so unique about you, that makes you stand out, and that the people in America should know about you?” I asked. “OK! I will write about my life in Homs!” It worked. Her application was accepted. Her visa was issued by the U.S. embassy in Jordan. Her Facebook message was full of joy and she message me: “I want to kiss Obama!” Noura is now studying architecture in Massachusetts. Last year, she managed to get her mother to the U.S. as well.

I am forever in debt to Noura’s family, for they supported me with the last cent of their money, opened their home for me when they themselves lost their home and never failed to show me love when their own life was desperate.

What became of Hani is a tragedy. Long before the war, he had applied for a student visa to study business administration in Germany. He spoke German, was deeply interested and had a fat bank account to fund himself. However, the young deputy manager felt humiliated when the embassy rejected his application with a mocking smile: “So you love Germany huh?” Feeling that he was seen as an infiltrator planning for a dark deed in Germany rather than a potential knowledge seeker, the sneer and the rejection tremendously damaged his dignity, and he vowed to never return to the embassy again.

When the civil war broke out in 2011, one of his friends in Europe told Hani that his girlfriend could fake a marriage with him and bring him to safety. He declined the extraordinary support, thinking that the war would not make Syria collapse to the level that he would have to run for his life. It turned out he was utterly wrong, as the war not only chased him out of Aleppo, but he was in danger trying to cross the city border, which opposition forces controlled at that time. He had to change his family name, since it could raise suspicion that he was Alawite. He could not get back to his parents’ house in the Alawite heartland and stronghold of Latakia, so Hani stayed briefly in Homs and became distressed. He told me his final wish: “Mai, I just want to die, on the green field of my parents’ farmland, with two cows grazing peacefully nearby.”

In 2014, Hani’s brother-in-law — the “mindless demon” who peed in his pants every night — was killed in combat and never saw his newborn sons.

At the beginning of 2015, the U.K. rejected Hani’s visa application. After a long time pondering the idea, Hani decided to escape illegally through Turkey. The smugglers put him and other Syrians in several different taxis and took them to the middle of a jungle, then jammed 48 of them in a locked minivan in the burning sun. Squeezed like sardines in the box, they were told to keep silent. Hani was lucky to find a loose screw; he removed it and put his nose next to the hole so he could breath. One man begged for a drop of water, then became motionless, but nobody could care for him. After a long drive, several long walks and many hours of silent waiting, all without food or water, they arrived on the Turkish shore and there was a small inflatable boat. There was no captain. The one put in charge was one of the asylum seekers who had zero experience. The smugglers told 46 people on the rubber boat: “Look! Over there you can see a light. That is Greece. Just go there, head towards that light.” Then they walked away.

The boat entered the angry water, shaken furiously, and soon the fuel started leaking out, together with the water flushing in. Covered in petrol and high waves, people recited Quran in their last hope to survive. One man was seriously burnt. He kept crying and suddenly threw himself into the sea, choosing death over pain and agony. Hani became unconscious, and didn’t know that the others then decided to turn the boat back to the Turkish shore after four hours of struggling and not getting closer to Greece’s light. When they washed up on the shore, some boat survivors viciously shook him awake. They jumped in joy when they saw Hani come back to life: “I told you! He is not dead!”

Hani is now back in his parents’ house. He lost all his savings and is deeply devastated. I tried to give him as much moral support as I could, but it has reached to the point that I sometimes feel the hesitation to get back to him. I am angry at myself, for I am powerless. I feel guilty of letting him die piece by piece each day. There is not much I can do other than recalling with him every little detail of the good time we had in Aleppo, the color of the sky, the taste of the food, the noise of the market, the laughing on the street. Bringing back the memories makes Hani happy, since it takes his mind off the harsh reality.

Other friends in Damascus keep struggling as the civil war destroys their homeland. Many bars and nightclubs have closed down but hard-core partygoers still can rock their nights away. The rest of the revelers now come home before 9 p.m. and party on Facebook. The war and its madness have become a new normal in their everyday life.

*Image: A girl in Damascus. Photo via author.