Fred Korematsu. A name more foreign than familiar to Muslim Americans. Born in Oakland, California on January 30, 1919, Korematsu’s American citizenship was gained through birthright. But, his Japanese ancestry and phenotype labeled him as an alien outsider, and then as a member of an “enemy race” following the Pearl Harbor Attack on December 7, 1941.

Decades before the modern “War on Terror,” Japanese-Americans, like Korematsu, were considered as the national security threat, despite being citizens and permanent residents, and many with deep roots in the United States. Race and racism in World War II America not only trumped the citizenship rights of Japanese-Americans, but also knotted them to the war crimes of a purely foreign threat.

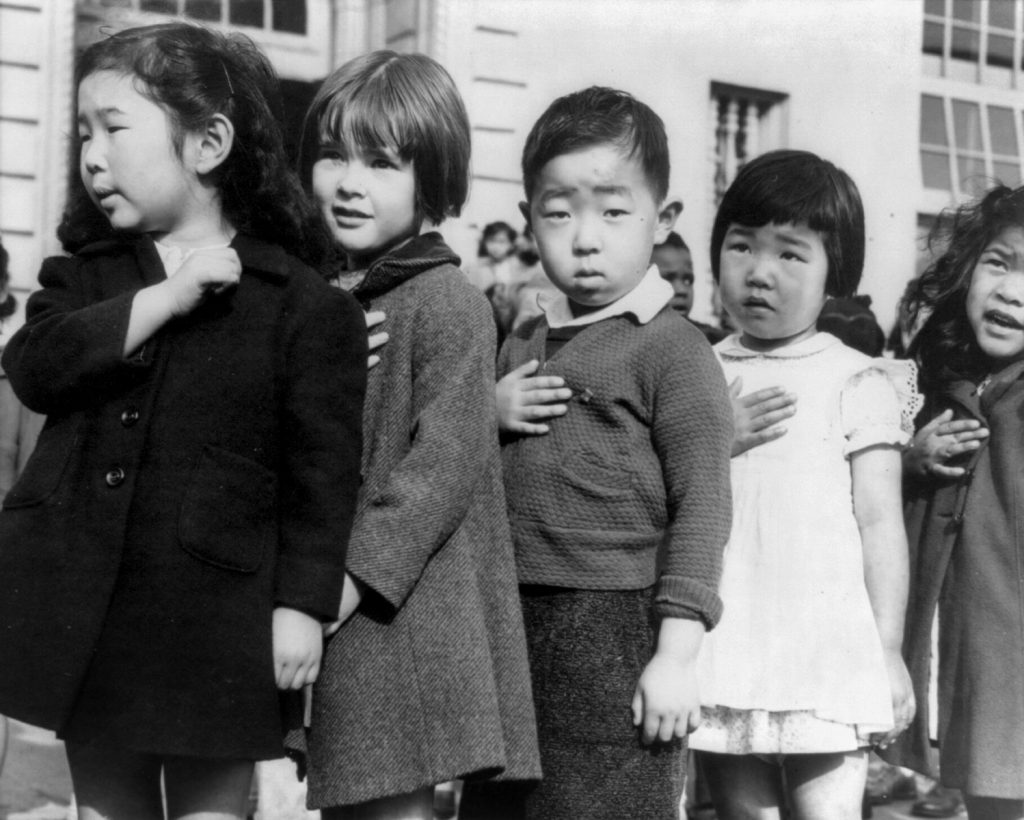

Children at the Weill public school in San Francisco pledge allegiance to the American flag in April 1942, prior to the internment of Japanese Americans. Source Wikipedia/CC

Three months after the Pearl Harbor Attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, equipping the military with broad power to relocate and place Japanese-Americans in internment camps. Approximately 120,000 Japanese on the West Coast were interned, 62% of whom were American citizens, while the other 38% permanent residents were denied citizenship on grounds of racially-restricted naturalization laws.

Fred Korematsu was not one of 120,000 confined within an internment camps. Instead, he resisted internment both on the ground, and ultimately, in the Supreme Court.

Today, the racial and religious indictment of the Muslim-American identity, which emaciates citizenship and the rights that emanate from it, mirrors the demonization of Japanese bodies more than seven decades ago. The transcendence of Korematsu’s resistance – between unspeakable state and societal racism, and beyond the most criminal form of collective punishment – offers a lurid example of courage for Muslim-Americans.

While neither Muslim nor modern, Fred Korematsu is a special sort of Muslim-American hero; An unsung civil rights icon that faced kindred evils that stripped Americans citizens of their civil liberties. Korematsu offers a model that not only inspires, but also instructs Muslim-Americans in their modern civil rights struggle.

Internment: Yesterday and Tomorrow?

The baggage of Japanese Americans from the west coast, at a makeshift reception center located at a racetrack. Source Wikipedia/CC

The terrorist attacks of September 11th spurred discussion of Muslim-American internment. Surprisingly, there were many proponents of rounding up and incarcerating Muslim-Americans, particularly amid the hysteria directly following the attack. If the strident views of pundits and politicians compounded with rising racism and Islamophobia did not strike enough fear in the hearts of Muslim-Americans, the precedent of Japanese interment evidenced that the rhetoric could rapidly devolve into reality.

An ever-looming possibility that another terrorist attack involving or implicated Muslims could come to pass. Muslim-American internment, fictionalized in the 1998 film The Siege, would seem too draconian a policy for the modern era. Yet, U.S. PATRIOT, Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR Program) and Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programming together function to criminalize Muslim-American bodies on grounds of free-exercise, phenotype, association and speech.

If Muslim-Americans are not already interned within the walls of their homes, mosques, community centers, or confined on America’s streets, another large-scale attack may bring about en masse, concentrated Muslim-American internment. Perhaps remote, the sum of pernicious legislation, still-rising anti-Muslim bigotry, and most saliently, the precedent of Japanese interment, places that possibility firmly in the center of the collective Muslim-American psyche.

A Model for Muslim Leadership

Although Islamophobia is ubiquitous and steadily intensifying, a number of Muslim-American activists and leaders have braved forward. In the spirit of Fred Korematsu, this leadership speaks unfiltered truth to power, and in the face of surveillance, phone-tapping and blacklisting, challenges the government encroachment on Muslim-American civil liberties.

During an impasse when elements of Muslim-America are racing to become part of establishment networks that subjugate Muslims near and far, a broad array of Muslim-American women and men have taken government persecution head on. And, in doing so, emulated the selflessness, strategy, and spirit of Fred Korematsu.

Korematsu laid a vivid blueprint of steadfast, principled and fearless resistance which provides Muslim-Americans today with giant footsteps to follow, and even bigger shoulders to stand on, while confronting the shared rage of state-sponsored and societal animus.

Indeed, the honor of “Muslim-American hero” should not be measured by faith or fatwa, race or rhetoric, but rather, impact. The trail of resistance and principled leadership blazed by Korematsu inspires and empowers legions of Muslim-American leaders today, and will ignite scores more needed for the daunting struggles that lay ahead tomorrow. While the precedent and prospect of internment looms strong, the model and might of Korematsu stands just as strong.

“Korematsu Day” is yet to be officially named an American holiday. But Fred Korematsu is a Muslim-American civil rights hero. Those words may appear juxtaposed, particularly since Korematsu was not a Muslim, but this civil rights giant’s impact on our community makes January 30th a Muslim-American holiday.