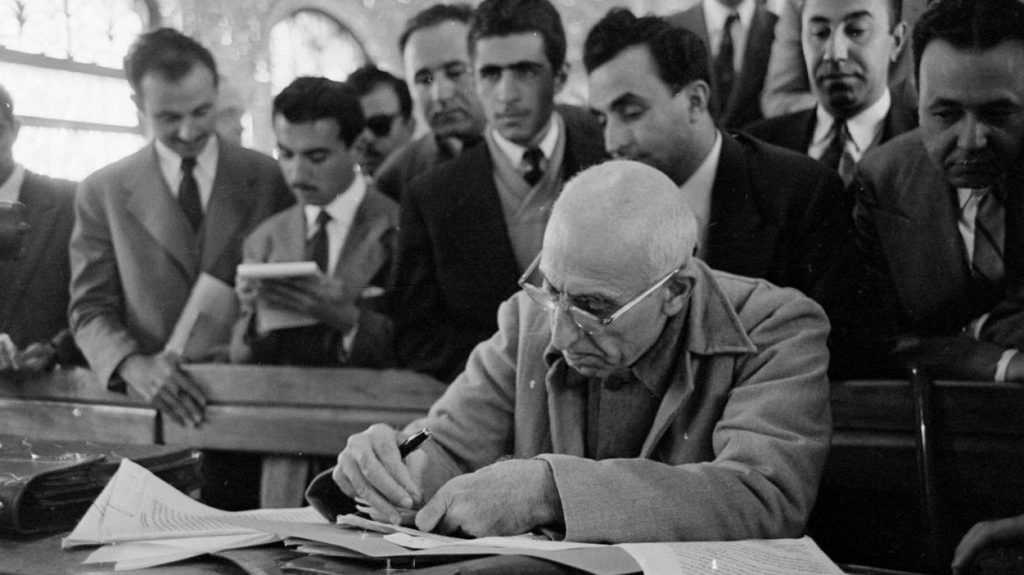

Earlier this summer, the U.S. State Department released a long-anticipated retrospective volume of documents detailing the CIA-engineered coup that ousted Iran’s celebrated Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953. The latest collection of memos and diplomatic cables chronicle “the use of covert operations by the Truman and Eisenhower administrations” to overthrow the popular prime minister — who successfully nationalized British oil assets in Iran — and restore the rule of a Western-friendly autocrat on the peacock throne in Tehran.

Nearly 65 years later, as historians and academics begin to sift through the updated records, the allure of regime change in Iran has not strayed far from the White House. Most recently, it has been reinvigorated by Donald Trump’s presidency.

Undermining the nuclear deal

President Donald Trump’s stated policy toward Iran has long been ambiguous and subject to platitudes and sudden shifts. On the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and six world powers — U.S., Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — Trump initially told Fox News that as a businessman, he likes “to honor deals,” but within months declared that his “number-one priority” would be to dismantle the “disastrous deal” with Tehran. Since his inauguration, Trump’s opposition to the accord — which prevents Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon in exchange for its reintegration into the global economy — has become a cornerstone of his time in office. But lost amid all the charged rhetoric, Trump has now twice certified Iran’s compliance with the agreement, just as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) regularly has since the deal was implemented last year (most recently here). On the whole, while the Trump administration moved to put Iran’s government “on notice” shortly after taking office, the White House has since articulated little in the way of policy.

This lack of a comprehensive strategy is reportedly wreaking havoc within the administration. According to numerous news reports, Trump was reluctant to recertify Iran’s compliance with the nuclear accord in July despite the counsel of his senior advisers. “He had a bit of a meltdown,” one official said of Trump, when the president was forced to extend the deal for lack of a way out. Soon after, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Trump suggested that his administration was prepared to not recertify Iran’s compliance again in September. Instead, according to Foreign Policy magazine, the president has entrusted a unit of aides with conjuring up a case for America’s withdrawal from the agreement.

As demonstrated by his departure from the Paris climate accord, rails against trade deals like the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and defunding of U.N. programs, Trump has disavowed the multilateral approach to addressing pressing international issues. In 2013, at the outset of the nuclear negotiations, President Barack Obama famously acknowledged “America’s role in overthrowing the Iranian government during the Cold War,” and sought to allay enduring fears by stating that his administration was “not seeking regime change” in Tehran. In 2015, after nearly two years of dogged diplomacy between several world powers and Iran, many viewed the announcement of the nuclear accord as an opportunity to begin a new chapter of relations between Tehran and many Western countries. But by repeatedly undermining the deal, akin to his campaign against the Affordable Care Act, a recalcitrant Trump is threatening to undo years of progress toward normalizing relations with Iran’s government. Such a move would signal a significant shift in policy toward Tehran, one that critics argue is geared toward confrontation and ultimately regime change.

Pressuring Tehran

As a citizen and then a candidate for office, Trump decried America’s historical role in overthrowing foreign governments and promoting democracy abroad. He routinely criticized the disastrous 2003 invasion of Iraq, and in July, he shuttered a CIA program to arm and train anti-regime forces in Syria. In December, shortly after being elected president, Trump declared that his administration would “pursue a new foreign policy that finally learns from the mistakes of the past. We will stop looking to topple regimes and overthrow governments.”

This has not been the case, however, when it comes to Tehran. Just days after Iran’s presidential elections in May, when nearly three-quarters of the electorate turned out to vote, Trump flew to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, to instead call for Tehran’s isolation. In June, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson testified that the administration would look to support “elements inside of Iran that would lead to a peaceful transition of that government.” That month, The New York Times reported that the CIA had assigned a new head of the agency’s Iran desk, signaling “a more muscular approach to covert operations” like the one that deposed Mossadegh. To top it off, important figures in the Trump campaign, including Rudy Giuliani, Newt Gingrich and John Bolton, who have all reportedly vied for positions in the White House, have been parroting the agenda of the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq (MEK), a traitorous and illegitimate cult dedicated to overthrowing the government in Iran.

To be clear, none of this is taking place in a vacuum. Forces backed by both sides continue to battle in violent proxy wars across the Middle East. In recent months, there have been several skirmishes involving the American and Iranian navies in the Persian Gulf. Additionally, the Republican-dominated Congress in Washington has been particularly receptive to Trump’s aggressive posturing toward Iran, and voted last month to authorize additional sanctions on Tehran. Iran declared the sanctions a breach of the nuclear agreement and responded by test-firing a rocket into space.

This ongoing scenario of retaliatory measures could quickly escalate into a serious confrontation, particularly in the absence of a bilateral channel of talks established as a result of intense nuclear diplomacy. Various reports suggest that the White House is looking to provoke Tehran into withdrawing from the deal, perhaps by demanding access to sensitive military sites that Iran would almost certainly reject. By jeopardizing the nuclear deal, reinstating sanctions and rejecting diplomacy, Amir Handjani of the Atlantic Council contends that Trump “could force the Iranian leadership to believe that nuclear weapons are essential for their survival.”

One-man show

Unlike the early 1950s, however, when British interests aligned with Washington’s to make the coup of Mossadegh a reality, America is now alone is considering an alternative to Iran’s current government. The prevailing view among European leaders is that the nuclear accord offers an inclusive model of engagement that could further promote dialogue and help stabilize conflicts in the region. Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia have all heavily invested in Iran since last year, and in recent weeks, French President Emmanuel Macron has emerged as a key defender of the agreement. Earlier in August, Federica Mogherini, the EU’s foreign policy chief, attended the inauguration of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in Tehran, where the incumbent called for the “mother of all negotiations, not the mother of all bombs.” Mogherini has long sought to safeguard the agreement from Trump’s onslaught. “There should be no doubt that the EU stands firmly by the deal, which is a multilateral endeavor,” she wrote in The Guardian this year, but it remains unclear exactly how far European leaders are willing to go to ensure the deal’s survival.

Catherine Ashton, the EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, and Mohammad Javad Zarif, the foreign minister of Iran, during the E3/EU+3 Iran talks. > Flickr/UN Geneva

Even in Washington, where anti-Iran sentiments run high, the memories of the invasion of Iraq remain particularly potent. As two experts on regime change recently explain in the Washington Post, “the United States’ troubles in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria are typical. Regime change often backfires. It does not improve relations. And it triggers civil wars that can draw the intervening nations into costly quagmires,” as illustrated by Trump’s recent decision to increase the U.S. military’s presence in Afghanistan.

Still, the president’s readiness to withdraw from the nuclear agreement has not wavered amid consultations with Washington’s military brass and key foreign policy advisers. Earlier in August, David S. Cohen, a former deputy director of the CIA, warned that despite “the aftermath of the episode regarding weapons of mass destruction in Iraq,” the White House may again attempt to politicize intelligence reports to support its belligerent policy toward Tehran. “If it’s politicized, that credibility and reliability is undermined,” he told CNN last week.

Ali Vaez, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group, recently wrote in The New York Times that a decision by the Trump administration to “escalate regional tensions, deepen sectarian rifts, undermine the nuclear agreement, pursue regime change and eschew all diplomatic engagement would be a hazardous affair,” and risks “breeding another generation of enemies” in Iran.

In Trump’s provocative statements, many Iranians cannot help but recall 1953, when the U.S. and Britain moved to quell Iran’s budding democratic movement and laid the groundwork for revolution in 1979. As the White House prepares for a confrontation with Tehran, the international community would do well to look back to the lead up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and restrain the Trump administration from igniting another futile conflict in the Middle East.

*Image: Former Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. >Via Iran Review