Editor’s Note: This article appears in our Winter 2016/2017 issue, and was written before the Quebec mosque shooting and recent bomb threats made against Muslim students in Montreal.

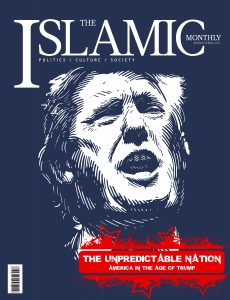

There’s a lot of talk about how the international order is fraying today as right-wing populism and ethnic nationalism continues to sweep through democratic societies. Yet by “international order,” nervous centrists with whitening knuckles really mean the neoliberal consensus that’s dominated the global economy since 1989, when “the end of history” was supposed to have begun taking shape and eventually arrive at everyone’s doorstep. The failure of this utopic vision has given way to, among other things, the success of Donald Trump, which has emboldened racist reactionaries everywhere.

This is true even for Canada, a country which, according to The Economist, now holds “the torch of openness” in the West. Trump’s rise precedes serious electoral threats to the centrist equilibrium in several European democracies, including Germany, Italy and France. Canada, with its photogenic Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and supposedly more porous border, has since been pushed by the flag bearers of the liberal establishment as the remaining bastion of multicultural tolerance in the West. And yes, the official rhetoric of the Trudeau Liberals contrast in stark ways with the rising tide of nativist sanctimony around the world, but the health of a society’s fabric is more than the lip service of its political elites.

Trump’s electoral success has given a newfound validation to sections of the West (particularly in North America) that have long been told to keep their nativist opinions away from the public square of internationalist liberalism. Trump’s win has smashed this assumption as, for instance, the former executive of Breitbart News, a leading proponent of essentially fake news and far-right opinion, is now a top adviser to the president of the United States. This kind of transition has practical repercussions and implications beyond the halls of power. In Trump’s case, the implications and subsequent effects also reach beyond national borders.

Trump’s campaign took political dog whistling to the point of utilitarian abuse. It was like watching a criminal wield his knife so liberally as to filet an entire room of people whereas a simple incision would have sufficed. Issues like security, immigration, law and order, and free trade, among other things, were addressed and exaggerated to such an extent as to amount to a permanent distortion of how these issues will be discussed. This shift in general rhetoric on a host of urgent problems have coincided — if not facilitated and abetted — the rebranding efforts of many on the right who’ve tried to undergo superficial makeovers to re-enter the public sphere.

Steve Bannon, Trump’s key adviser. Flickr> Gage Skidmore.

This, for the most part, is why the term “alt right,” a catch-all neologism for a network of dog whistling right wingers, has entered public language: to refer to and present a rebranded form of not-so-closeted White supremacism that’s been emboldened by the widening cracks in the neoliberal order. Its reach isn’t limited by national borders or trade tariffs, and its cultural influence has been brewing in Canada as much as any other Western liberal democracy that offers access to the internet. Whether this translates into more political or electoral success is another matter, but the reality of its sociocultural emergence and emboldening is quite obvious.

The clearest indication of this is the parallel emergence of conservative politicians in Canada who’re clearly looking at Trump’s victory as some sort of ideological and political blueprint. They think that they too can present themselves as populist men or women of the people who want to remove the elites from power. It helps for clarity’s sake that members of the Conservative Party of Canada are soon going to vote for a new party leader. Several participants of this race have revealed in their own ways how much Trump-like rhetoric they’re going to appropriate to win.

Member of Parliament Kellie Leitch, one of the more visible candidates, sent out an email to her supporters right after Trump’s win in November to exalt the unexpected victory as an “exciting message” that Canada could also benefit from. According to her message, which was also posted on her Facebook page, the Americans were bold and courageous enough to “throw out the elites.” She then follows up by saying that it’s going to be the same message that she’ll be bringing to her campaign for party leadership and, eventually, to the race for prime minister.

About a month later, The Rebel Media, a Canadian cognate of Breitbart, hosted a rally in Edmonton, Alberta in front of the provincial legislature to protest Premiere Rachel Notley’s proposed plan to impose a carbon tax. About 1,000 people showed up to yell “Lock her up!”, a clear reference to chants by Trump supporters against Hillary Clinton. Chris Alexander, another CPC leadership candidate, spoke at the rally but later was said to have noted that he “felt uncomfortable” with the chants, presumably because he doesn’t like being linked with the connotations of Trump campaign. He should have thought twice then about attending a rally organized by an outlet that likes to assert, among other things, “How the left pushes paedophilia.”

Then there’s self-proclaimed billionaire troglodyte Kevin O’Leary of Dragon’s Den and Shark Tank fame, who openly says that Trump’s win had inspired him to pursue a political career. Like Trump, it’s likely that O’Leary isn’t really a savvy business genius, but plays one on TV. The list of prospective Trump wannabe goes on for a few more names, but this kind of political effect in Canada has set off its own dog-whistling “chain” of sorts.

CPC leadership candidate, center left, was formerly on the TV show Shark Tank. Flickr> Disney | ABC Television Group.

High-profile politicians send obvious and not-so-obvious signals (e.g., Leitch’s email) to their potential supporters in an attempt to mobilize segments of the masses that understand what they actually mean. Once these people receive the message, they in turn dog whistle to others, as the layers of this network become further and further removed from the center of public life, which is reserved for people like Leitch and Alexander, as far as the “alt right” in Canada is concerned. The outermost layer, then, is the really ugly stuff, which has also been rearing its head in Canada.

A look at Canadian university campuses, where right-wing recruitment and activism have been known to flourish from time to time, is enough to set off alarm bells. In the past few months alone, racist propaganda, along with other right-wing paraphernalia, has been found on several major campuses, including the University of Toronto, the University of Alberta, Ryerson University, York University, the University of Western Ontario, McGill University and McMaster University, among other campuses.

Many of these incidents took place right around the time Trump won the election, signifying the long-awaited normalization of right-wing rhetoric that’s long been confined to the fringe pages of Breitbart and other niche spaces. This newly branded sort of populism makes the politics and attitudes of President George W. Bush’s era, exemplified by outlets like FOX News, appear rather tame in comparison.

Such a shift, as indicated by the aforementioned campus activity, won’t just be reflected or represented in official electoral politics. It’ll also encroach upon the broader spectrum of national and local institutions, which are influential spaces where the regulation of rhetoric/speech has always been a reflection of the national political climate.

The extent to which such institutions in Europe, Canada and, above all, the U.S. will be tested remains to be seen. Things will appear with more clarity during these first days in the Trump administration, though his choice of Cabinet hasn’t inspired much hope as far as moderation is concerned. Moreover, and perhaps even more importantly, the chaos unleashed by the general breakdown of an establishment-oriented façade isn’t novel to modern history. It’s the same kind of unraveling that led to global conflict decades ago and, if the past is any indication, there are plenty of regional conflicts — from the Middle East to the South China Sea — that can spark something of even greater proportion.

Except this time, the man in charge of the greatest military presence in human history likes to tweet at 2 a.m. and, as fate would have it, also keeps the nuclear codes.

*Image: A protest against anti-terror legislation in 2015 in Toronto. Flickr/Eric Parker.