Uruguay opens its arms to Syrian refugees

JUAN LACAZE, Uruguay — Three teenage siblings amble down the grassy shoulder of the central road in this rural Uruguayan town, about two hours from the capital Montevideo through green landscapes so tranquil, one remembers that this nation of 3.3 million residents affectionately refer to it as a “big village.” Mohammed, 15, is lanky, cheerful and popular. Passersby give him a thumbs up and yell his name as he and his sisters carry pots of homemade dulce de leche and corn desserts that they hope to sell to local teachers at the school where about half of his siblings study.

At the entrance to the school’s patio, a young Uruguayan girl angrily slaps him on the face. He seems not to find the gesture unwarranted, and quickly explains himself to her in an accent of Spanish unique to the Southern Cone of South America, a breathy and wide-mouthed variety he’d picked up in less than a year in the country.

Merhi Alshebli with three of his children at their home in Juan Lacaze. He says that he would farm if he had more land. He has barely a hectare right now. >Taylor Barnes

Mohammed’s family of 15 brothers and sisters is the only Muslim family in this town of 12,800 residents and modest pastel-colored homes, and seemingly the only foreign-born one. They’re one of five Syrian refugee families who were granted asylum in Uruguay in 2014. After selling several pots of sweets, the siblings stream back to their airy house to a series of “¡hola!” Mohammed’s brother, Ahmed, grabs a phone to take a family selfie: “¡uno dós trés!” His sisters pass around an invitation card to a birthday party of a classmate named Pilar.

Their father, Merhi Alshebli, slumps in the couch, a red keffiyeh atop his deeply furrowed face that speaks to his years as a migrant construction worker in Jordan. He turns and begins to describe why, just days earlier, he had doused himself in gasoline and threatened to set himself aflame as he argued with social workers from the host country where his children were so quickly making a home, but which he was begging to leave.

He says he’d rather go to Britain or, as unbelievable as it sounds, even back to Syria. The difference there, he says, is that he has friends and expects profitable job prospects.

“Uruguay,” the exhausted father says, “it’s all lies.” For him, that means the land that was supposed to be enough to farm on is so small, a person can walk across it in 30 seconds. The work opportunities the family does have pay far too little for their pricey bills. One time, his teenage daughter worked 22 days caring for an elderly couple and earned about $80. He feels stuck; he had been told that he could travel on to places like Argentina, but later found that there was little will to grant visas to Syrians who hold only an Uruguayan travel document.

Alshebli himself left Syria years before the war started, but his family, originally from Aleppo, fled in 2011 just when the conflict began to heat up, and spent four years in refugee camps in Lebanon.

“Uruguay? Uruguay?” said Nada Alshebli, 19, imitating the cluelessness she felt about the place when delegates from the small South American country asked her family if they’d like to move there from those camps. “We heard it, but: Uruguay?”

A consultant for the government delegation said the younger members of the refugee families looked up the country online the night before their interview with the team so they would know where it was.

A unique experiment

Uruguay is a quiet country that, if it’s known to outsiders, it is for its obscurity. Under socialist President José Mujica, a former political prisoner, the small nation punched above its weight in global politics, grabbing international headlines for bold and progressive policies and turning the tranquil country the size of Oklahoma into an icon for the Latin American left. It legalized marijuana, same-sex marriage and abortion — radical moves in heavily Catholic Latin America — and, in addition to the refugee families, opened its doors to six Guantánamo Bay detainees whom the U.S. struggled to resettle, as it was too dangerous for them to return to their home countries. While European nations have sealed their borders to asylum-seekers and Americans overwhelmingly support imposing severe restrictions on allowing in refugees from the Syrian conflict, off-the-map Uruguay stepped up to the plate in a proactive way by announcing that it would invite a total of 120 Syrian refugees in two waves. Rather than risk Mediterranean boat crossings or wait years for security clearance to enter the United States, the five families — the first of the two planned cohorts — arrived in Uruguay in a matter of weeks, a journey the Uruguayan delegation arranged for them in October 2014.

The resettlement of the refugees was a unique experiment in transcultural empathy, in which goodwill and individual willfulness has been put to the test. Though Uruguayans broadly expressed goodwill toward the families, the refugees came into a country that is largely homogenous. It is made up of Western European descendants who pride themselves on secularism. It’s also a place where policy is often neater than practice. Two years after the country made headlines for legalizing marijuana, it’s still not available for legal sale. When a U.S. military transport plane carrying six Guantánamo detainees arrived in December 2014, the men had access to free medical care but no official Arabic translator to help them navigate the system.

When the exhausted refugees arrived, they received an enthusiastic official welcome. The families smiled for news cameras as they disembarked and met President Mujica in the airport, and were escorted by a motorcade to their new homes. Neighbors waved the blue-and-white Uruguayan flag while one of the resettled young men waved the soccer jersey of Uruguayan footballer Luis Suárez.

But the families’ friction with their new home would soon try the patience of the people who received them. First came accusations that a member of the Alshebli family had committed an act of domestic violence against another relative. While no one was charged with an offense and Uruguayan officials did not detail the nature of the incident, the family was sanctioned by the refugee relocation program and had a portion of its stipend cut. Then, neighbors accused a second family of not sending its daughters to school, an issue that Uruguayan authorities said they addressed and resolved.

The use of head coverings in public places like schools provoked debates in the country that are now routine in the West. In an editorial, former President Julio María Sanguinetti, from an opposition party, questioned why Muslim women had been allowed to take ID photos while using head coverings, calling the hijab a symbol of “female subordination.” The difference between historic migration waves that formed the South American nation and this current one, he wrote, was that “those corresponded with our same values of living in harmony and this [new migration wave], on the other hand, corresponds with concepts that are totally distinct from those of human rights and essential liberties.”

The outsized attention paid to the refugees (in a country whose own journalists admit that little news happens) meant that their unfavorable incidents were covered and discussed in a way that other individuals would not expect theirs to be.

Six months after the first families arrived, Mujica’s successor, Tabare Vazquez, said the government would conduct “profound analysis” before accepting the second planned cohort of refugees.

Then, in an extraordinary move, one of the families fled the country in August 2015. The Aldees family got as far as the airport in Istanbul, where family members were detained and deported back to South America. They later told the media that they had hoped to migrate from Turkey to Europe. The idea that the father was willing to part with his savings for plane tickets and trade a legal refuge for a perilous future in migrant-weary Europe seems to push the limits of rationality. However, he told local media that he saw no future for his children in the pricey country where there were few job opportunities. Despite his failed attempt to leave the country, he still wants to move to Lebanon, Turkey or Jordan.

Discontent continued to bubble through September, when the five families protested in front of the president’s office in Montevideo, asking to leave the country for the same economic reasons that led to the Aldees’ and Alshebli’s desperate actions.

A gesture gone awry

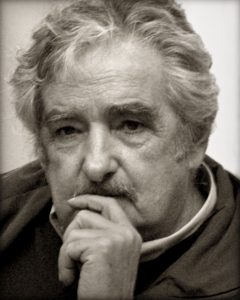

Jose “Pepe” Mujica >Flickr/Vince Alongi

Mujica, whose term ended in March 2015, responded to the public strife in September with the class rhetoric native to his ideological camp.

“I asked them to send me peasants and they brought me middle class, relatively comfortable people,” he said on national TV.

However, Merhi Alshebli, the one who doused himself in gasoline, said he would farm if he had more land. He has barely a hectare in Juan Lacaze.

As far as selling homemade snacks, his daughter Nada said it’s hardly profitable. “The people here are poor. They usually can’t buy,” she said.

Three other families contacted by The Islamic Monthly declined to be interviewed after what had been months of public strife and negative press. While Mujica’s social class explanation does not seem to stack up, at least in the case of Alshebli’s humble and hardworking family, seeing the families’ strife through the lens of a cultural mishap also seems to only tell part of the story.

Samir Selim, an Egyptian imam of one of two mosques in Montevideo, said expressions of extreme prejudice against Muslims do not occur in Uruguay the way they do elsewhere in the West. Speaking in the Spanish he had learned in only eight months in the country, the gentle-voiced imam said secular Uruguayans and observant Muslims are able to live side-by-side, even when the latter are clearly a minority. (He estimates the Muslim population of Montevideo to be 300 — mostly diplomats and their families.) But he still saw the refugees as living on borrowed time, and expected them to return to their home country after the conflict there ends.

But if we look at past migration waves, Selim could be mistaken. Arabs are no stranger to Latin America; the story of the century-old Syrian-Lebanese diaspora across the region is often told as one of migrants who integrated, prospered and rose to the top rungs of their societies. Their descendants include Mexican telecom billionaire Carlos Slim Helu, the world’s second wealthiest man, and Colombian pop star Shakira, whose name means “grateful” in Arabic. Some 10% of Brazil’s Congress is made of lawmakers with Arab ancestry. The population of Lebanese and their descendants in Brazil are now more numerous than the population of Lebanon itself.

As the refugees in Uruguay occupied a spotlight in the South American media, their trials took on outsize weight, and the seeds of both solidarity and prejudice took root.

In a dim convenience store near the entrance to Juan Lacaze, a bus line employee and the store clerk are quick to share their thoughts with a visiting reporter on the Syrian family in town. Both are bothered by what they see as a dependence on government welfare in a country that is not their own. Pointing to a photo of a sweet-faced young woman with Down syndrome, the convenience store clerk said her daughter’s disability check was far less than what she needed to survive.

She asks not to be named as she speaks frankly about her Syrian neighbors, adding that she believes that members of the family judged Uruguayans for wearing short clothes in the summer. “They were uncomfortable because they thought that going to the beach was scandalous,” she said.

But she adds that her comments are only her perception. Still, they raise the question of what extent the culture clash is real or perceived by either party, and how conversations about Islam and the values associated with its practitioners are taking place in Uruguayan society, pushed by the public debate over the resettled refugees and Guantánamo detainees.

“These issues were very far from Uruguay 10 years ago. Not now,” said Susana Mangana, an academic who took part in the Uruguayan delegation that interviewed the refugee families in Lebanon.

The lesson to be learned from Uruguay’s experience with these refugees, Mangana said, is that victims are not perfect. They also are not defined only by their losses but also by their desires and ambitions, just like the members of the societies that receive them.

“There is no ideal refugee like there is no ideal country,” Mangana said. As one of the country’s only academics with deep knowledge of the Middle East and Arab culture, Mangana has been a frequent commentator in the national media as Uruguayans tried to make sense of their new neighbors.

The current friction came about when hopeful expectations did not match reality, she said, and examining this experiment in a new type of multiculturalism is useful for proudly progressive Uruguayans, too.

“People are refugees but they are also still human beings with their own dreams to fulfill,” Mangana said.

Despite Merhi Alshebli’s exasperation, he also seems eager to show the ways in which he was making inroads into his new locale, just like his children. He proudly shows off his garden, tight rows packed with radish, cabbage and mint, and says he actually understands Spanish better than he speaks it.

Then he laughs as he taps his head and physically twists his tongue to explain what happens when the words he understands try to make their way out of his mouth.

This article appears in the Winter 2015/2016 print issue of The Islamic Monthly.

The magazine can now be purchased with print on demand! Purchase a single issue here.