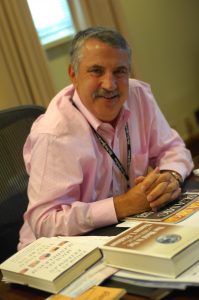

Thomas Friedman Interview

Thomas Friedman is perhaps one of the most influential public intellectuals in the world. His writings cover a range of subjects, from foreign policy to energy policy to globalization. One of the themes permeating many of Friedman’s recent writings involve trends he recognizes as affecting America’s global competitiveness. Ever the canary in the coal mine, Friedman has synthesized the national and global political and economic landscapes to make sense of why America is where it is and how it can get better, or worse, depending on what it addresses on a number of a critical issues. Given the upcoming elections, we asked Friedman to give us his thoughts on America and its future with the Muslim world. Beginning with energy and playing out a number of scenarios, Friedman walks us through the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East and beyond as it relates to the United States. We also focus on what ails America and how that affects democracy at home.

SCENARIO ONE: AMERICA LEADS IN ENERGY TECHNOLOGY

THE ISLAMIC MONTHLY: Let’s start with energy – specifically the future (or not) of U.S. energy. For the sake of discussion, let’s focus on the next 10 to 15 years. You focus on thinking about energy in geopolitical terms, energy technology (ET) as the next global industry, as opposed to fossil fuels, the finite oil resources of the Muslim world. In 2008, you gave an interview saying America just needed five years to take the lead in green technology. It’s now 2013. Where do you think we are right now and where will America land with regards to technology over the next 10 to 15 years?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: So we’re better and we’re worse, in a way. Better off than I expected in some ways and worse off than I expected. We’re better off in that thanks to hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, we found a way to unlock America’s huge natural gas potential. Today, natural gas now outstrips coal as the leading provider of electricity in America. If this is as big as people believe it is, natural gas will soon be powering trucks and marine ships. Maybe even standard commercial cars that people use at home through compressed natural gas, other gas to liquids. The potential is there for more energy independence by America and a reliance on cleaner fuel – natural gas emits half as much as coal, in terms of carbon emissions. That’s a real bounty. At the same time, we’ve gone backwards in a few ways. Climate denialism is stronger than ever today, stronger than it was in some ways four years ago. The great thing about cheap natural gas, again it’s cheap, and it provides a cleaner alternative to coal. But it’s still a fossil fuel, and because it’s still a fossil fuel, it still emits carbon. What we want is natural gas to be a bridge to a cleaner energy future, not a dam against a cleaner energy future, not a dead end. To get this right, to get the most out of it, we not only have to make sure we exploit natural gas in a clean way – it’s a challenge – but we also have to make sure that we are instilling and implementing all the incentives to win solar, nuclear energy efficiency that will make them continually competitive with natural gas in the future. That’s kind of where we are right now.

TIM: Let’s create a scenario; let’s say America takes the lead in ET. What would change in the relationship between the U.S. and the Middle East?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, it’s a very good question, Nobody really knows. What we do know is that the planet is going from 7 billion people today to 9 billion. More people want to live like us, drive American- size cars, live in an American-size home, and eat American-size Big Macs. What does that mean? It means that energy demand is going to be going up. Even if America tomorrow – and it won’t happen overnight – but if we did reduce our demand for gas and natural gas and crude oil by a significant degree, that does have an exponential effect on producers in the Middle East, everything else being equal. But if China’s demand is growing and India’s demand is growing, they are not going back. Pakistan’s demand is growing, Iran’s demand is growing. I don’t think the price of oil will go to $5 a barrel, but it could well go to $50 or $60 a barrel from around $100 now. Since most of these governments budget their oil, they make their budget on oil, say at $85 a barrel, it could, on the face of it, have a very negative impact in the short run. People and government have a lot less income. In the long run, it has a very positive impact, because when you can’t rely on sticking a pipe in the ground, what you have to rely on is unlocking the energy and talent of all your people – men and women. What is the most entrepreneurial country in the Middle East today? It’s Lebanon. Which country has no oil or gas? Lebanon. The same was true of Israel, the same was of Bahrain. You could see a real gradation. Turkey, for instance: no oil and gas, very entrepreneurial. You can either dig your future out of the ground or you can unlock the potential of your people. There would be a transition though, and to me the smart thing that governments there would be doing right now is taking their oil and gas fountain – and the smartest ones are to some degree – and making sure they’re investing in their people to unlock their potential – men and women.

TIM: But if in the event that America does take the lead in ET to the extent that fossil fuel prices do fall, what happens to the U.S. relationship with oil-producing countries in the Middle East? Would America pull out entirely?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: There is still Israel, there is still China and India. Oil is a tangible commodity, so there is a global market. The fact that we may need less may affect the global price because we’re big consumers: we probably take about a quarter of global demand. But if suddenly, let’s just use a crazy example, fighting in the Middle East led to the closure of the Strait of Hormuz and no oil could get out through the Strait of Hormuz, well that would affect China, India, Europe, it will affect the whole global economy. It will affect us, too, then. I don’t think the question is do we come or do we go? I think the question is how deeply and energetically engaged do we remain? When you phrase the question that way, I think it’s conceivable that we will be less engaged. But then if we are, do we really want to say, “Oh China, you now take over in the Middle East.” We, geopolitically important countries, tend not to do that.

TIM: Right, will it create a vacuum?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Right, or, “India, we want you to do that.” I honestly think it will affect America’s activism in the Middle East at the margins, but I don’t see it as fundamentally, “Well you all, it’s been fun and I will see you later” and the “We’re just going to go and live off our natural gas.” I don’t see that happening.

TIM: In the scenario that interest will decline due to both the combination of the use of natural gas and also other renewables, and say there are other interests in the region and some other parts of the globe that might be more dependent on the old oil infrastructure, how does the Arab Spring affect that–the development of the relationship between extracting countries versus the Arab Spring. How does that reality in the region play out along this negativist scenario that we contemplate?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, as again, it’s really complicated, that’s a three-corner shot, so it’s hard to really know for sure. We are interested in change and reform in the Middle East but in a stable way. We had a story in the New York Times yesterday about how we are actually more dependent on Saudi Arabian oil for different market reasons in the recent months. But let’s imagine a situation where our own dependence on Saudi oil went to zero, which is OK. Will we then say, “Yo, Saudi people, rise up and revolt against the ruling family”? I don’t think so. There is this stability of Saudi Arabia. Our desire is to see reform there but happen in a stable but steady way. I don’t think that interest changes just because we are less dependent on oil. I think our interests remains, for our sake, for the sake of the region, for the sake of the people of Saudi Arabia or Kuwait or the United Arab Emirates.

TIM: But doesn’t that stability kind of depend on both the price of oil and also the steady demand of oil delivery, isn’t that stability pinned to maintenance of the status quo in terms of infrastructure?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, it is and it isn’t. I mean, how stable did Bahrain turn out to be when you don’t have reform? How stable did Libya turn out to be, when you do not have reform? So, I think precisely what we are getting over is this notion that stability and the status quo go together. I don’t think that stability and the status quo go together at all, not in a flat world where people are integrated, where women are assuming new roles, where young people want to be consulted and participate. I think the trick is to open up, move down the path of reform, do it in a way that is consistent with your own society’s stability and culture, and just don’t think you can do nothing.

TIM: What would be the foreign policy implications in the Middle East? What else does the Middle East have to offer in 10 to 15 years, after the oil is no longer useful?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, first of all, the Middle East would always be an important trading partner in just a market sense, like America is a big market for us, Asia is a big market, Europe is a big market. You are going to have hundreds of millions of consumers there, from just a standard market point of view, from a very narrow American point of view. I’m a radical pro-immigration advocate. I’m not saying we just look at the Muslim world or we just look at China, we just look at India as a source of our talent. But, one thing we know . . . first or second generation or new immigrants or children of immigrants have started about 40% of the Fortune 500 companies. For me it’s always been a really very important issue that I want this country to be open to the most energetic and talented people from around the world. All one needs to do is just to go to any hospital in America and see the number of Pakistani or Indian or Lebanese, or Syrian, or Egyptian doctors, who are either first generation or themselves immigrants, to know, and I’m a big believer — brains are distributed evenly around the world. What aren’t distributed evenly are opportunities, stable government, educational institutions, etc. And it’s so obvious that, I don’t know what the average income of Muslim-Americans is, but Muslim-American immigrants of recent vintage, I bet they have a very above-average representation in professional and business occupations. It doesn’t have to be American in particular, and women in particular. I’m not saying, again, we’re just going to look at the Arab world, “You can fail, and we’ll just take a straw and just kind of now slurp up your best people.” But to me there’s no reason these countries can’t thrive if they put in place the institutions that create the kind of trust that build the kind of societies that produce productive people. That is why I have been in favor of the Arab Spring and all of these things.

TIM: Aside from human capital, what else could you envision that would be?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, I don’t have the statistics but it’s in a column that I did, called “About Oasis500,” which is a start-up group in Amman. But let’s talk about the Arab world for a second, which I know best. I believe the number of Arabic speakers in the world is a huge number, well over a billion people speak Arabic. I believe that Arabic content on the Web is about 1% or 2%. I was in Amman, Jordan, and I did this column about a group called Oasis500, whose goal is to have 500 Jordanian start-ups, in a year or two years. My feeling, my experience is, again, it’s all about the framework you put in place. Why is it Muslims from Pakistan or from Egypt come to America and thrive, and they are frustrated back home? It’s about clean government. It’s about a rule of law. It’s about intellectual property protection. They’ve got all the talent and energy of anybody else. As new immigrants they may have more of it, so you put them in our system and they become doctors, lawyers, and businessmen and entrepreneurs. You keep them in a system they have, some will become doctors, some become lawyers, some become businessmen. But will they realize their full potential in a system where you have to bribe somebody to get a license or a birth certificate? Will they realize their full potential in a society where the electricity is off 12 hours a day? Will they realize their full potential where the stock markets are rigged, where your intellectual property can’t be protected? I don’t think so. That’s our greatest advantage, so you install those things in the big Muslim states, I think you will see an incredible entrepreneurship.

TIM: If America does pull out, what happens to the nature of governance in the Middle East given that the United States requires the petro-dictators. What is the native Arab response. . . and in light of the Arab Spring, the Arab sense of identity?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Right. I don’t think the Arab Spring had much to do with energy. I think it was just the opposite, in fact. I think the Arab Spring happened because particularly young people knew they were living in a context where they could not realize their full potential, that they are being kept down by their own governments.

TIM: All the petro-dictators.

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Yeah, those governments were all petro-dictatorships for the most part, either directly or indirectly, they benefit from it.

TIM: Who may be upheld by America’s interest of fossil fuels in the Middle East.

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: That’s not just conjecture, if you read my book, that’s a fact. We were the funders of petro-dictatorships. We treated all these countries as basically big, large gas stations: Libya station, Iraq station, Iran station, Egypt station, Syria station, and all we asked of them were three things: Keep your palms open, your prices low and don’t bother Israel too much, and you can do whatever you want to your own people. You just do it out back where we don’t have to see it. So you can keep your women down as much as you want. You can deprive your young people of whatever opportunities they want. You can preach whatever crazy ideas in your newspapers or elsewhere that you want. That is why, to me, 9/11 happened, because 9/11 was the distilled essence, I mean Bin Laden, Al Qaida, was the distilled essence of all the bad things going on out back. The people, they have to take a lead as they did in the Arab awakening. Hopefully we can find a way to help them. But if you don’t change that context of what’s going on out back, then nothing will change. That’s really been my belief all along, it’s why I very controversially supported the Iraq war, not for WMD reasons but for democracy reasons. I wanted to get rid of a terrible dictator and give Iraqis a chance to shape their own future. It was a hugely costly war. We made every mistake in the book. We created a huge amount of damage. But Iraq today does have a chance to shape its own future. They may not do that, or this generation may not do that. But maybe the next one will, I don’t know. They may try and fail, and stumble, get up and fall back. But I’ve always believed the world would be a better place if more people everywhere have a chance to shape their own future and realize their full potential. I think that is what life is about. When people get frustrated, it’s when they feel they are living in a context that deprives them of dignity, deprives them of justice and deprives them of the freedom to realize their full potential, and that to me is what the Arab awakening was all about. I think it applied to every country, and so I have been an unmitigated supporter of it. It may go through a more conservative Muslim phase before it comes into another phase. People are going to try different things out. They may try on the Muslim Brotherhood for a while, see how that fits and how it feels, but if the Brotherhood doesn’t deliver for the Egyptian people, they will be out just like Hosni Mubarak was out, I am convinced of it.

TIM: So, the Arab Spring will still maintain its grassroots?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t know but I am trying to be very humble about it. It’s like the Arab awakening was like watching elephants fly: something you didn’t expect, something you haven’t seen before, “Wow, elephants fly.” I have a rule about elephants flying: Whenever I see elephants flying, I shut up and take notes. I am being very humble about the Arab Spring. There’s kind of a competition out there, you might have noticed, of who can be the first to say the Arab Spring is going to fail. Everyone says, “I told you so, I told you so about the Muslim Brotherhood.” I have no desire to tell anyone anything. I don’t know. I’m just listening, watching. It may turn out all these people are right, they may be wrong. They may be right this year and wrong next year, by the way. I’m just trying to listen day to day, figure it out. Trying to draw red lines around things that I think will lead in a bad direction. Build bridges to things that I think are going to lead in a right direction, I mean intellectual bridges, in my column. I don’t think I need to be a part of this race.

SCENARIO TWO: AMERICA REMAINS DEPENDENT ON FOSSIL FUELS

TIM: So let’s create the alternative scenario. America is still very much dependent on fossil fuel, so who would be the leader in ET in this instance?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, obviously China is clearly taking the lead in some areas, but when it comes to the most advanced innovation, it’s still America. I think if we really took the lead the way I talked about, then everyone will follow. Others are doing it, anyways, but not at the speed, scope and scale it would be if we had a real competition, not for who can be the first to put a man on the moon, but who could actually create the technology so men and women can stay here on Earth. A kind of global competition, that way. That’s really what I have been advocating. Just by market forces, we can go back to that image of 7 billion people going to 9 billion people, more of them want to live like us. That means energy demand is only going one way. It is going to be a great business, so are we going to be in that business? Is Pakistan going to be in that business, is India, is China? I don’t know. All I know is it’s going to be a great business and only a fool would not want their country to be open to those opportunities.

TIM: Does the relationship with oil-producing countries change with America? Does it change or is it essentially static? How does the emergence of that leader affect the relationship of that country and the U.S. and Middle East?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I think because of the Middle East’s centrality to global geopolitics, that we would not want to see another hegemon — Russia, China — move in and, may I go back to what I said earlier? I could see us playing a slightly smaller role but I would not see us abandoning the region and just say “Oh,” like I said, “China, Russia, it’s yours now. Global focus is just on our hemisphere.” I don’t see that happening.

TIM: What about America’s military expenses, then, for operations in the Middle East–the security that goes into the region to maintain our hegemonic control over the region? I mean, is that just going to keep growing?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, I think that’s not going to keep going upward and upward because we can’t afford that anymore. So that’s going to find its limit and the combination of our budget needs at home and the fact that we find more domestic sources of energy. I think those two things together would suggest a lessening of the American role in the Middle East, but how much less, I can’t say.

TIM: What about the rest of the world? Russia and China, for example, are trying to make deals with Iran, so what would happen to our relationship with other countries when competing for the possibility of leadership in the region?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I think that competition will exist even if we discover more oil. We’re never going to know how much we have, or how long will it last. You are always going to want to have diversity of supply. I think the Middle East will remain a region of competition, of global competition, fighting for a long time.

TIM: How about the evolution of the Arab Spring? Will that change in the instance that America is still very much dependent on fossil fuels?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I think that the drama of people rising up demanding their own freedom is one that resonates very deeply with this country. I think that President Barack Obama has tried and would like to find a way to relate to the Arab Spring, but I think he also wants to be, rightly, very careful that we don’t take it over. It is very important that they own this. He is trying to influence it this way but without, “We’re so never going to go to the extreme of Iraq and putting boots on the ground again.” I doubt, Syria, notwithstanding. But I think what we should be doing is taking all our military aid to Egypt of $1.3 billion and converting it to economic assistance, particularly educational assistance. I think we should say to Egyptians, we think this is about these young people who feel frustrated not realizing their full potential. Every year we are going to take $100 million off the Egyptian Army budget and we will build with it science and technology high schools, from Aswan to Alexandria. That’s going to be our American aid now. No more guns, no more, we’re just going to build schools in partnership with the Arabs and Muslims who have the teachers and have the students, etc. We will help fund any school, anyone who comes up with a business plan for it.

ON AMERICAN DEMOCRACY

TIM: This goes to the question about American democracy, in particular, whether the profit-seeking of a few is capable of preventing the greater benefit of the many from taking place. Chris Hayes came out with a new book about the end of meritocracy. He argues that democracy is not working in America because the people who succeed end up creating the infrastructure that keeps them as an elite class. I know you mention income inequality as a hindrance to our ability to work collectively. You say it “threatens to fracture the body politic in ways that could undermine our ability to do big hard things together.” What do you say about this end of meritocracy?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t know the specifics, but I think it is something we have to be aware of. I’m a fanatic and I think there is only one way to close the gap, and that’s education. We are entering a hyperconnected world where every boss now has more access, cheap access to cheap labor, cheap genius, cheap robot, cheap software, and then this world averages over. There is only one answer to that, and that is to get everyone as close as possible to some form of post-secondary education, it could be vocational, it can be liberal arts, it can be science and technology. But in a hyper-connected world where average is over, there is one thing we know absolutely for sure: Every good job will require more education. If I were advising President Obama, since he’s the one running, I would have made his campaign very simple. I promise that in four years, I will get more Americans, as many as I possibly can, the opportunity and access to some form of post-secondary education. I want more of them to graduate high school with the skill-set of post-secondary education and I want more of them to be able to obtain that post-secondary education. This is the only way we are going to close the income gap. I mean, you can say the lead should be more of this or more of that. I would have to look at the specifics of what Chris Hayes is talking about, I am sure he is right about some of this. But the unemployment rate today for people with our-year college degrees is 4.1%, which is almost none. That’s people switching jobs basically. That tells you that education is the only way up and the only way out. If that is the fact, then we’ve got to get more of it for more people.

TIM: In this scenario, that the idea is that once you are elite, you basically exist in a space that continues to promote this elitism. It’s very self-perpetuating. Would you think that this is the reason why America fell behind in not taking the lead in ET?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t know. I think there are different kinds of elites. I think there are venal elites, and self-interested elites, and selfish elites, and I think there are visionary elites. I can think of many people I know who built charities or businesses to help disadvantaged people, or schools. I’m talking about starting with Andrew Carnegie — who is an elite, who you could say gave us public libraries — to any number of people today who are trying to give back. I can think of some really venal and selfish elites, so I just don’t think you can generalize: If you are an elite, that means you do X, Y, and Z. There are elites that are real leaders and role models. There are elites that are really selfish and want to pull up the ladder once they’ve reached the roof.

TIM: If you look at almost every part of the American network, they are what you want to call selfish elites or vested in their interest. If you look at how the policy has gradually shifted over 34 years despite the fact that Americans have been functioning relatively well, there has been a dramatic change in the way people choose their president or congressman. Is that a fundamental challenge to American democracy?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: The reason that we are becoming less equal is because of the greater requirements, secure requirements, for a good job. This goes back to the ’80s basically, this started changing as globalization and the IT revolution merged, and each started to drive the other. What did we do? We said, “Jeez, we got a lot of people who really don’t have the skills to. . . ” By the way, I’m not just talking about writing software. I don’t mean everyone needs to be Steve Jobs. If you want to get an advance machine tool job today, you need to know calculus. We know a lot of people don’t, we can’t expect everyone to know calculus, what do we do? We created a huge bubble that created a huge number of jobs to build houses and to be in retail. You don’t have to have a lot of skills to work in the new Gap store that opened, at the latest Starbucks branch, or to hammer a nail for a new house. So what this bubble did was actually give a bias about a decade or decade and a half even, where we took the lowest skilled part of our population and we actually gave them decent jobs. They were able to sort of advance economically. Then we ran into a wall because of what happened in 2008. Now there is no bubble in construction, there’s no bubble in retail, so these jobs where people who didn’t have globally competitive skills worked are not easily available, and that’s why the unemployment rate for people with no college degree is 13%. Whatever the causes of this, and an economist can debate that until the cows come home, we know the cure — 4.1% unemployment for people with four-year college degrees. About 7%, I think it is, for two years. It’s very, very clear — it’s education, education, education. Again, people tend to put a little bit of a conspiratorial gloss on this. You walked into this office an hour ago from that elevator. When I came to this bureau in 1990, we had a receptionist who sat out there. We don’t anymore, she lost her job. But she didn’t lose it to a Mexican, she lost it to a microchip. We got voice mail. Most jobs are outsourced to the past, they aren’t outsourced to India or Mexico or Pakistan or anywhere else. They are outsourced to the past. Now I suspect that the woman who was there 15 years ago, if she is still working, she has probably added skills along the way to move herself up the chain. That’s what everybody has to do. It’s easy to kind of say it’s the elite that’s putting you down. Well, it wasn’t really the elite, technology will do that. I was in San Francisco last week, I technology of the electronic checkout machine. That’s now the entry-level job, that you oversee a bunch of machines by which customers will automatically check themselves out. It’s all about education. That doesn’t mean, again, that we don’t have venal elites, that people aren’t trying to rig the game, they are and those should be taken on in their own terms. But you go down a dangerous road when you say it’s all about that. It’s not about this if only elites weren’t venal. CVS wouldn’t have electronic kiosks. United Airlines wouldn’t be slimming down its work force, and The New York Times would still have a receptionist.

TIM: I guess the question was aiming more towards the robustness of that democracy where you have the winners bringing greater and greater advantage to the winners while the losers are playing catch up.

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I got it. I think that’s a real issue, I think it’s part of what this election is about. My mother-in-law says if you want to live like a Republican, vote like a Democrat. That if you are a part of the group that is doing well in this system, you owe it to yourself and to others to look out for them and make sure you are always building a ladder for others to join you. Otherwise, your wealth and your security will never be stable. So I don’t understand people who don’t look at the world that way.

TIM: About this question about democracy, given the fact that democracy is not being exported in the Arab world, how do you understand this argument in that context?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well the Arab world had a big problem of frankly venal elites. That is why these revolutions happen, because people didn’t think the opportunities were being shared fairly. There were clusters of cronies around these regimes who made off with huge amounts of money. That’s why Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia burned himself alive because the system was so rigged, so corrupt and so unjust. I think that these awakening revolutions will change that. The Arab awakening has been, up to now, a lot about freedom from dictatorial regimes — Syria, Yemen, Libya, Tunisia, Bahrain and Egypt. But once you got freedom from, then you need freedom to. Freedom from is about destroying things. Freedom to is about constructing things, constructing the rule of law. The institutions, the independent judiciary, the free press that ensures that The Islamic Monthly is free to work, publish, write whatever you want. Freedom to takes a long time, it’s really hard, we’re still working on it. I think that is really the enterprise that the Arab world is going to be engaged with for the rest of my life. First half of my life, hopefully this half, was watching them struggle with freedom from, but I think the next half, I’m going to watch them really wrestle with freedom to. How they build the frameworks to secure freedom to do these things.

TIM: A lot of people have talked about water as the next oil. So how do you understand that may underlie the world of geopolitical realities? Does it underlie all that?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: One thing that we know about Syria, and I wrote about this, is Syria is on the back end of basically a decade-long drought. Over the last decade, farmers and herders have been ravaged in Syria forcing them to give up and move to urban areas. This has put a huge strain on urban resources, and it’s surely one of the reasons for the uprising there. We also know that the uprising in Tunisia began in a month that set the record for world food prices, from the World Food Organization. We know that there is a connection between energy, climate, food and political stability. That has played out in the Arab awakening and is not done playing out.

TIM: And will America play a role in the water issue in the Middle East?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t know, I will tell you I am always a little skeptical on the water thing because I have been hearing that for 30 years, but one year it’s going to be true. With the rising populations, Yemen could be the first country in the world, or Sana’a the first major city in the world, to run out of water, that’s from Yemeni hydrological engineers and the United Nations. Sooner or later, all of these people, from 7 to 9 billion, all of them want to live like us, will be consuming so much more water that some of the societies will hit a wall without more sustainable environmental practices. That’s going to be a huge part of what, as they build their freedom to, how they factor that in.

AMERICA IN DECLINE

TIM: At what point do you consider that America started to get on that slow decline? I’ve recalled you stating at some point that much of it is linked to America not having an enemy or competitor — a “primary competitor” — like it did during the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Today, it seems that Islamic jihadists, and terrorists are the enemy, wouldn’t you say? Why isn’t this “enemy” of America playing or motivating the same type of competitive edge that had existed with the Soviets and America? Do you suspect this “enemy” will remain the enemy for long?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: Well, I don’t actually think it has been. I don’t think we replaced the Soviet Union with Al Qaida. I think we replaced, we should have, Soviet Union with the merger of globalization and the IT revolution. I think it’s that. That is the real challenge that we face today. Unlike the Soviet Union, it has no face, it has no missiles, but it is something that challenges every job, every city and every community. Eight years ago it was true when George Bush was running against John Kerry, they really tried to play the security card, the terrorism card, as a way of making the case that Bush will keep you safe and Kerry won’t. Of course it was ludicrous. But it’s just one of those motive issues that the margins could and did work. But I would say for the most part, if anything we’ve replaced, if you are looking for a geopolitical boogeyman, it’s been China, much more than Al Qaida, especially now that Bin Laden is gone.

TIM: If you were to draw a parallel of the Kennan Long telegram as having shaped the American foreign policy of the Cold War, what would you say is the “charter” for the wars existing in the Muslim world now, many of which have the hand of America? Is there a simple, outlined “charter” that might detail what the agenda is? What the threat is? What do you think is the long-term objective in the Muslim world with these wars? Why did we “overestimate” 9/11 to follow through on this foreign policy? What is the analog to the Kennan telegram for the war on terror?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t think we have one right now. I think we’re making it up as we go along and I think some of that maybe necessarily so. But I think we’re just making it up as we go along.

TIM: Some people argue that it could potentially be the Bernard Lewis article in The Atlantic, “The Roots of Muslim Rage.” Do you agree?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I don’t think so, no. I think the Arab awakening has changed everything and I think a lot will depend on what people there ask of us, may be nothing, it may be a lot. I think that really depends how they find their voice and what they see as their real interest, and hopefully that would be for more schools and not more tanks.

TIM: You talk about how significant the year 1979 was for a number of reasons, one of them being the Ayatollah’s coming to power in Iran, then the Meccan invasion by Sunni extremists. The result was a negotiation with the Saudi ruling class to allow the fundamentalists to spread their Wahhabi position, creating a scenario of competition of “Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia” in the world, with no well-funded moderate trend of Islam. The major significance, as you write about, is that they had oil wealth to “buy off any contradictions.” This goes to the question you pose of political Islam in a world without oil. How do you suspect this will take shape in the coming years and what role will America play in this?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I think no country is going to be immune from the Arab awakening because the Arab awakening is driven by deep human longing for dignity, for justice and for freedom. I think that applies to young people in Saudi Arabia as much as to young people in Egypt, Tunisia, or Yemen, or Libya, or Syria. If I were in Saudi Arabia, I would be getting ahead of this and looking for ways to appreciate those aspirations and align my country with them. I just don’t think a monarchy led by 75- and 80-year-old men in today’s modern world is really sustainable.

TIM: What’s one thing most people would be surprised to know about you?

THOMAS FRIEDMAN: I’m pretty much an open book. I am a fanatic golfer and golf nut. If I have three free hours any day, my first choice is to run to the golf course if the weather is nice.

—

Thomas L. Friedman is an internationally renowned author, reporter, and columnist – the recipient of three Pulitzer Prizes and the author of six bestselling books, among them From Beirut to Jerusalem, The World Is Flat, and That Used to Be Us: How America Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back.

Amina Chaudary holds a master’s degree from Harvard University in Islamic History and Culture from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She is earning a PhD at Boston University with a focus on Islam in America. She is the founder and editor of The Islamic Monthly