The Grand Bazaar is the heart of old Istanbul. It is one of the oldest shopping malls in the world, with more than 3,000 shops, store-houses, stalls, workshops — many in old Ottoman hans (hostels) — as well as a restaurant, a teahouse, several lunch counters and a bank, altogether employing more than 20,000 people. This center of Istanbul’s once-flourishing carpet trade is now fallen on hard times.

You enter the vaulted passageways of the labyrinthine Kapalı Çarşı (the “covered bazaar”) treading on polished flagstone and running the gauntlet of armed police who swipe at your bags with metal detectors — a regular feature of shopping centers in Turkey in these uneasy days of bomb attacks and heightened security concerns.

Shops selling like wares are grouped together, in streets named after the various guilds that did business here in Ottoman times. One of the oldest parts is the rug section, home to shops specializing in Turkish carpets and kilims, Persian, Caucasian or Afghani, and even — although they don’t say it — Chinese carpets masquerading as Turkish ones.

Avrupa Pasajı, an antique atrium with several colorful shops and vendors of traditional goods >Flickr/Miguel Virkkunen Carvalho

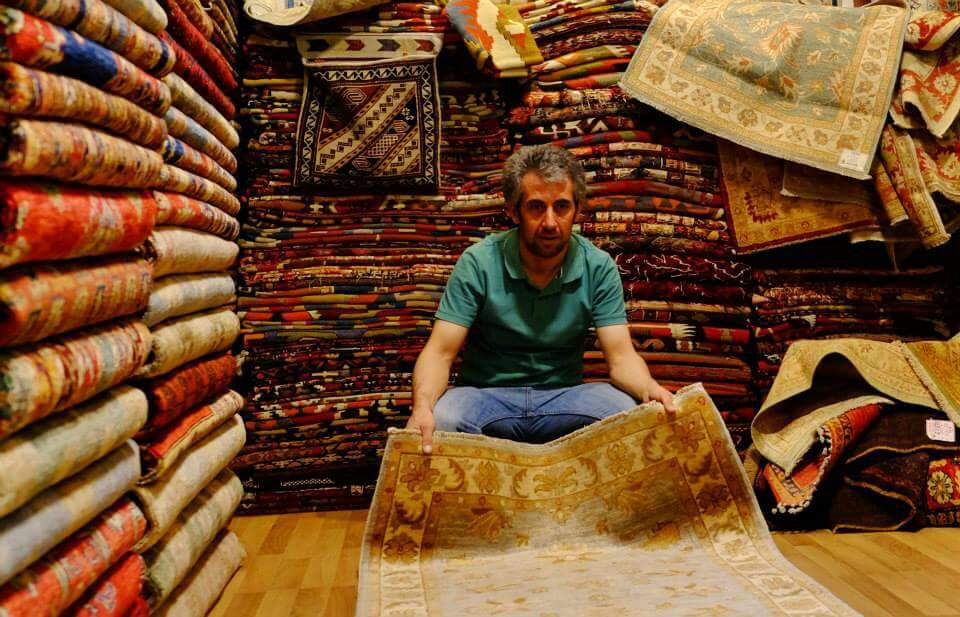

Each shop contains around 500 or 600 carpets, hanging from walls or lying folded in piles. Prices range from $200 for a handmade prayer rug to $2,000 for a silk-weaved Ottoman-style wall-hanging. The merchants stand outside, smoking and chatting, and trying to entice tourists in a variety of languages, offering glasses of tea to those who deign to pause before their shops, lured by the dealers’ come-on.

Each carpet tells a story, and the dealers are eager to convey these woven secrets — masters as they are in the art of salesmanship, fluent in several languages, often with university degrees, and worldly wise in a way that appeals to the well-heeled Western tourist. What is often not mentioned is the provenance of some of the antique carpets, and their long circuitous international peregrinations.

A Unique Breed of Salesman

At the center is Kalender Carpets, which has been in the bazaar for 60 years. The business runs in the family. Ziya Özalp, one of the employees, is a relative of the founder. Ziya is an Istanbulu of Kurdish descent who has been selling carpets professionally here for five years. His father was a rug dealer and so is his brother. When he finished university, Ziya went into the business.

For a long time, it was good work: You didn’t have to exert yourself too much and you met people. But with the political unrest in Turkey since last year’s attempted coup and recent bombings, tourists — who account for 90% of the bazaar’s customers — are keeping a wide berth of Istanbul and the bazaar. And so Ziya has plenty of time to talk about the secrets of the carpet trade over tea and cigarettes.

When you buy a carpet, you are not just buying an object; you are buying a story. >Ziya Özalp

Rug dealers are a unique breed in Turkey, Ziya says. “When you come to Istanbul or anywhere else in Turkey, rug dealers will be pretty much the most interesting people that you can see because they have to be a little more intellectual to impress you.”

Rug dealers have to be schooled in the art of the deal: knowing how to bargain, when to push the hard sell, when to use the old soft shoe. They have to have a convincing spiel and a charming, personable manner, which includes a capacity to talk about a wide array of subjects sometimes only tangentially touching on the carpets themselves.

Partly this is because the potential customer has to be enticed into parting with an often large sum. But it also has to do with the nature of the object itself: Carpets tell stories. “When you buy a carpet, you are not just buying an object; you are buying a story,” Ziya says.

Carpet dealers at Kalender Carpets in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar showing off their wares. >Photo courtesy of the author

Storytelling Rugs

Each antique carpet or kilim has a narrative behind it. Many are dowry carpets, made to be kept in a dowry box, whose colors and patterns tell stories about the women who made them, their tribe, their beliefs and the region they came from. Most Turkish carpets do not feature human or animal forms, as the Quran forbids this. Some of the rugs are prayer carpets created by a nomadic people in lieu of a mosque.

The tradition is going to die. It has already died. It died a long time ago. >A Turkish carpet dealer

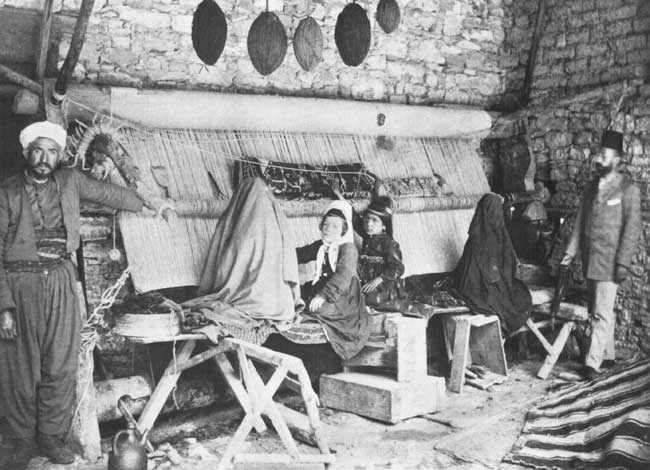

These days, the art of carpet making in Turkey is becoming obsolete. Up until 30 or 40 years ago, women in Anatolian villages made the carpets, particularly in the regions around Konya and Kayseri, where the tradition was passed down from mother to daughter. Often government banks would go to villages, donate looms and commission carpets. This practice has ended and today, there are fewer women weaving carpets in Anatolian villages, fewer people willing to work for $200 a month, which is impossible to live on in Turkey today.

Traditionally, Turkish weavers are women and girls. >Flickr/Anoop Rao

Some of the dealers from Istanbul go to China to buy carpets. The Chinese make their carpets in one month and sell them for $50 to $100. They are not only cheaper, but also are said to have a better weave. Today, just 20% of the rugs sold in the Grand Bazaar come from Turkey.

“The tradition is going to die,” says another dealer I speak to. “It has already died. It died a long time ago. The only thing the dealers have going for them is they sell to tourists. You go into a shop and it’s completely arranged for tourists. It’s based on a lie. A big lie. And whatever is based on a lie is going to lose one day. A lot of tourists, they come from different countries without any knowledge and they want to buy a Turkish carpet. They get sold something without checking and doing the research. One day they might find out it’s not from Turkey.”

Preserving a Traditional Trade

South of Istanbul on the Asian side is the small town of Hereke, lying on the rocky shore of the Sea of Marmara, surrounded by sleepy fishing villages and home to one of the last great bastions of Turkish carpet making.

In the town is a company of the same name that was founded in 1843. Four generations of carpet weavers have made carpets in the building (which is now a museum), using traditional Ottoman designs and washing their carpets in the natural water streaming down from the mountains and emptying into the sea. One of the current owners was born in the building, which 19 years ago belonged to the government before it was privatized.

There were between 60,000 and 70,000 weavers actively working for the company 20 years ago. Today, just between 5,000 and 6,000 people work for the company, weaving carpets for the domestic market as well as for customers as far away as the U.S. and Japan. The tradition is passed down from mother to daughter. In addition to traditional Ottoman designs, the company also caters to the contemporary tastes of the new rich.

The problem is the new generation. There is no new generation for production. We hope that we can produce for 10, 15 more years. In 20 years, we won’t be able to find new weavers. >Nurhan Ör, Hereke spokesperson

As a company representative, my translator and I sit drinking Turkish coffee in the Hereke showroom surrounded by photos of public figures who have received its carpets — including Pope Benedict XVI, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former U.S. President Bill Clinton — and framed letters of thanks from Buckingham Palace among other places, we watch as two women work a loom, making a silk carpet of refined quality, albeit of questionable, typically nouveau riche taste.

The carpet, half complete, depicts a gaudy contemporary poolside scene featuring scantily clad women, peacocks and potted palms, and is meant to hang on the wall in the home of an Istanbul fast food restaurant manager. This particular carpet — which measures about 6.5 feet by 9.8 feet — takes one-and-a-half years to complete. Each woman receives $400 per month for her labor. The price tag will be around $14,000, with the company making a $2,000 to $5,000 profit.

Hereke is struggling to compete with stiff competition from China, explains media spokesperson Nurhan Ör. To legally use the famous Hereke name, the Chinese have named a town “Hereke,” where Chinese-manufactured carpets come from.

“The problem is the new generation,” Ör says. “There is no new generation for production. We hope that we can produce for 10, 15 more years. In 20 years, we won’t be able to find new weavers. Either that or we pay $1,000 a month [to attract people to the trade].”

The market for antique Turkish carpets has also hit upon hard times. In Istanbul, Ali Kemal brings me to his stockroom in the bazaar quarter. He throws down antique kilim after kilim until there are several million dollars’ worth of rugs lying on the floor. All of which he can’t manage to sell.

“The new generation has different tastes. They have different interiors,” Kemal says. “The business is getting less and less profitable. The big dealers are doing something behind the carpets. The carpets are just the image.”

Turkish Carpets Hidden in Germany

Kemal makes me a proposition. It is a known fact that the best antique Turkish carpets are not to be found in Turkey anymore, but in Germany, in the households of Germans who traveled to Anatolia in the 1970s and bought up quality carpets in situ. When I return to Germany, I am to keep my eyes open for carpets and kilims on the market and call Kemal if I find something of interest.

An American goes to Istanbul and thinks that there must be antique carpets there. And there are. But he doesn’t suspect that it was bought there in the ’60s or ’70s, brought to Germany, repaired and sold again to a Turkish dealer in Germany. >Dr. Razi Hejazian, owner of Art Teppich Kelim

In Berlin, few carpet dealers want to talk on the record about their business. I did find Dr. Razi Hejazian, owner of Art Teppich Kelim in the upscale Wilmersdorf district. He came from Iran in 1986 to study dentistry at the Free University. Eventually, he became more interested in art and ethnography and in 1994, he opened up this gallery, which displays carpets and kilims acquired on research trips to the Middle East and Central Asia.

Dr. Razi Hejazian

The generation of German collectors who traveled to Anatolia in the 1970s and 1980s to buy carpets and kilims as part of the “kilim wave” is dying, Hejazian says. Many of their heirs have advertised their carpets on eBay and have been approached by Turkish dealers looking to cut a deal. Hejazian is one of 14 sworn experts on carpets in Germany, and people often consult him about the value of carpets that have come into their possession.

“If you go to auction houses in Germany, you’ll find only Turkish dealers looking to buy up carpets here and sell in Turkey,” Hejazian says. “I would venture to say that almost every antique kilim which is being sold in Istanbul comes from Germany. Every week I have two or three dealers from Turkey. They are hungry for Turkish kilims.”

The telephone rings. It’s a woman who has inherited a number of Turkish carpets and is requesting Hejazian’s consulting services. She recently advertised the carpets on eBay and Turkish dealers immediately descended like hawks, looking to cut a deal, and saying what she had was of no real value. But if they were of no real value, why the immediate interest?

It is indeed the case that you can buy pieces up here at a song and sell them in Istanbul for a great deal of money, Hejazian says.

“An American goes to Istanbul and thinks that there must be antique carpets there. And there are. But he doesn’t suspect that it was bought there in the ’60s or ’70s, brought to Germany, repaired and sold again to a Turkish dealer in Germany. That’s the circuit at the moment.”

*Image: A carpet shop in Istanbul. >Flickr/Vladimer Shioshvili

This piece appears in our Winter 2016/2017 print issue.

This piece appears in our Winter 2016/2017 print issue.